- About

- Programs

- Issues

- Academic Freedom

- Political Attacks on Higher Education

- Resources on Collective Bargaining

- Shared Governance

- Campus Protests

- Faculty Compensation

- Racial Justice

- Diversity in Higher Ed

- Financial Crisis

- Privatization and OPMs

- Contingent Faculty Positions

- Tenure

- Workplace Issues

- Gender and Sexuality in Higher Ed

- Targeted Harassment

- Intellectual Property & Copyright

- Civility

- The Family and Medical Leave Act

- Pregnancy in the Academy

- Publications

- Data

- News

- Membership

- Chapters

The 2022 AAUP Survey of Tenure Practices

Download:

Published May 2022.

Introduction

The tenure system is a ubiquitous feature of American higher education. Of the roughly 1,400 four-year institutions that the Carnegie Classification system categorizes as bachelor’s, master’s, or doctoral institutions, 87 percent reported in the 2020 Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) survey, conducted by the US Department of Education’s National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), that they have a tenure system. From the perspective of AAUP policy, having a tenure system is essentially just a matter of granting tenure, which the AAUP defines as an indefinite appointment terminable only for cause or under extraordinary circumstances, such as financial exigency. However, the tenure system is now generally identified with having a system of reviews that lead to a tenure evaluation.

While tenure practices vary among institutions, systematic studies of these variations are rare. The institutional survey component of the National Study of Postsecondary Faculty (NSOPF), also conducted by NCES, included questions about tenure practices the four times it was administered between 1988 and 2004, and Cathy A. Trower’s 2000 study of faculty handbooks and collective-bargaining agreements, Policies on Faculty Appointment,1 analyzed the prevalence of several additional features of the tenure system at that time. However, not only are these existing studies dated, but they do not address features of the tenure system that have come into focus more recently, in particular those related to diversity, equity, and inclusion.

The present study provides information about the prevalence of general tenure practices and policies, including accommodations related to family obligations, as well as considerations of diversity, equity, and inclusion as they relate to the tenure process. Some of the survey questions were taken from NSOPF in order to allow comparisons of how these features have developed over time. Other questions were included to capture recent developments in the tenure system. Yet another set of results provides information about the extent to which tenure continues to be threatened by institutional policies and practices, such as post-tenure review programs and replacements of tenure lines by faculty on contingent appointments. The results of this study can inform discussions on individual campuses about potential changes to prevailing tenure policies, practices, and standards.

This study is intended to be generalizable to the roughly 1,200 four-year institutions that have a tenure system and a Basic Carnegie Classification of doctoral, master’s, or bachelor’s institution. The study thus excludes two-year institutions and four-year specialized institutions, such as freestanding law schools, art institutes, and seminaries. In the following, we generally refer to the group from which the sample was drawn as “four-year institutions with a tenure system.” The questionnaire was administered to a random sample of 515 chief academic officers and had a response rate of 52.8 percent. For additional methodological information, please see the appendix.

The Probationary Period and Stopping the Tenure Clock

The central innovation of the 1940 Statement of Principles on Academic Freedom and Tenure was a probationary period of fixed length, after which any full-time faculty member who is reappointed has tenure, regardless of the faculty member’s rank. Before the 1940 Statement, tenure was generally tied to rank, most commonly to that of full professor. Faculty members at lower ranks therefore could serve indefinitely on annually renewable, full-time positions until a possible promotion to a tenured rank. The maximum length of the probationary period is seven years under the 1940 Statement, which means that the tenure review should occur no later than the sixth year in order to provide adequate notice in case of nonreappointment.

The present survey finds that 96.8 percent of four-year institutions with a tenure system have a probationary period of fixed length. In 2004, according to NSOPF, 90.5 percent of the same type of institutions had fixed-length probationary periods—a relatively small change. The mean length of the probationary period was 6.3 years in 2004, compared to 5.7 years now. The tenure review thus generally occurs right around the six-year point, as the 1940 Statement recommends. These two findings, like those in a 2020 AAUP survey on the prevalence of standards related to academic freedom and due process, which reported that three-quarters of four-year institutions with a tenure system base their academic freedom policy on the 1940 Statement, demonstrate the lasting impact of this eighty-year-old statement on US higher education.2

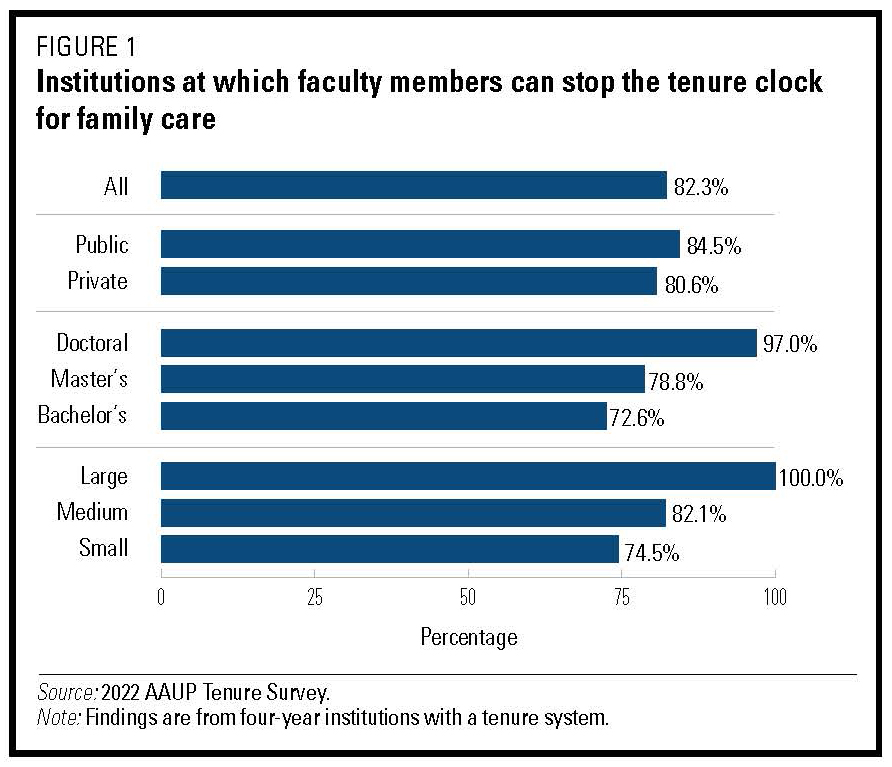

Over the last fifty years, the inflexible, fixed nature of the 1940 Statement’s probationary period has raised concerns about how faculty members with family obligations pursue tenure within a reasonable amount of time given that childbearing age for many faculty members tends to coincide with the probationary period. In 2001, the AAUP issued a statement recommending that institutions allow probationary faculty members to stop the tenure clock “for up to one year for each child,” with a maximum of two times. “Stopping the tenure clock” is a bit of a misnomer, because in cases where faculty members do not take leaves of absence, the practice doesn’t so much stop as extend the probationary period by an additional year or two. Immediately before the AAUP issued that recommendation, Cathy Trower’s 2000 survey of faculty handbooks and collective bargaining agreements found that 17 percent of four-year institutions with a tenure system permitted the stopping of the tenure clock for health or family reasons. Today, 82.3 percent of institutions provide this opportunity, which represents a large shift in institutional policies over the past twenty years. Of those that offer policies to stop the tenure clock, 92.5 percent make the option available to faculty members regardless of gender, in recognition that partners can be coequal caretakers of newborn or newly adopted children. Only 50.5 percent of institutions explicitly permit stopping the tenure clock for elder care; however, many respondents stressed in their comments that their colleges and universities provided opportunities to negotiate stopping the tenure clock on an individual basis for many or unspecified reasons.

Some of the results in this report will be broken down by Basic Carnegie Classification (bachelor’s, master’s, doctoral) and institutional size, which is based on Carnegie categories as well: small (fewer than two thousand students), medium-sized (between two thousand and five thousand students), and large institutions (more than five thousand students). The availability of options to stop the tenure clock varies among institutions of different Carnegie categories and sizes, with about three-quarters of small and bachelor’s institutions providing the opportunity, compared to all large and essentially all doctoral institutions doing so, with medium-sized and master’s institutions falling in between (see figure 1).

The ubiquity of policies to stop the tenure clock notwithstanding, the long-term, disparate, and gendered impact of such policies on primary caregivers has been noted for some time, as women are known to be more likely to stop the tenure clock for childbearing and child-rearing and thereby delay promotions and concomitant raises in base salary, which has a compounding effect over time.3 There certainly is a need to look for alternative arrangements that avoid this result.

Tenure Quotas and Standards

At some institutions, the percentage of faculty members who can be tenured at any given point is limited by a tenure quota, a mechanism originally proposed in the 1970s to address a perceived problem resulting from the spread of the tenure system: institutions considered to be “overtenured” were thought to face financial challenges and limited flexibility to respond to the changing circumstances of that decade. One result of tenure quotas is that probationary faculty members at institutions that have them would not be granted tenure, regardless of whether they met the substantive requirements, if doing so would result in the number of tenured faculty members exceeding the tenure quota. At the time, the AAUP issued a policy statement opposing tenure quotas, in which it characterized this outcome as “nullifying probation.”

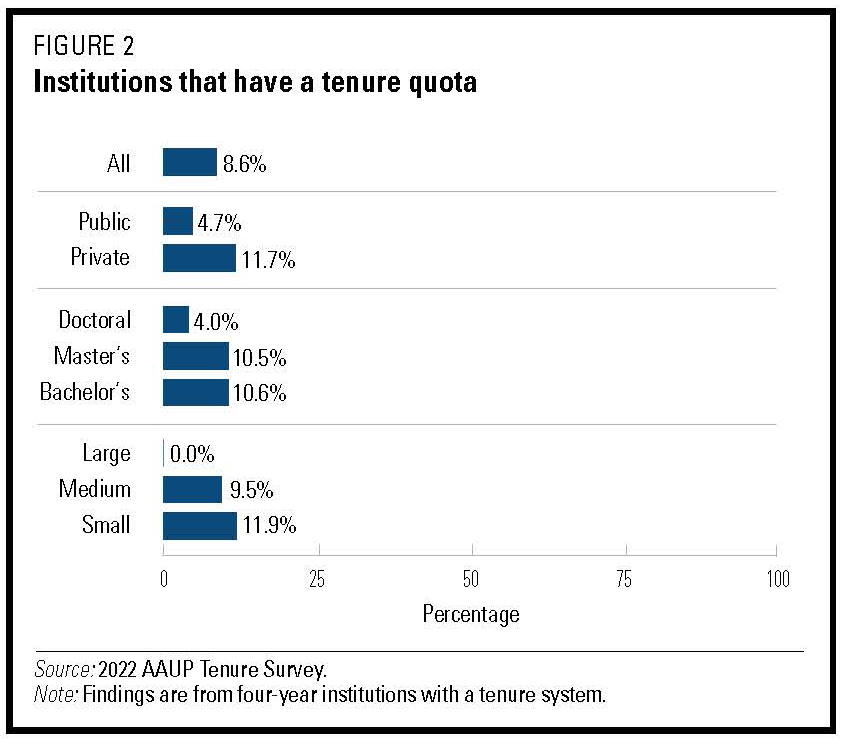

In 1988, when the question about tenure quotas was last included in the NSOPF institutional survey, 17.8 percent of four-year institutions with a tenure system reported having either formal or informal tenure quotas. Now formal or informal tenure quotas can be found at 8.6 percent of institutions. The prevalence of tenure quotas has thus been reduced by about 50 percent over the past three and a half decades. Moreover, only small and medium-sized institutions reported tenure quotas in the present survey, and such quotas were more prevalent at bachelor’s and master’s than at doctoral institutions (see figure 2).

In 1988, when the question about tenure quotas was last included in the NSOPF institutional survey, 17.8 percent of four-year institutions with a tenure system reported having either formal or informal tenure quotas. Now formal or informal tenure quotas can be found at 8.6 percent of institutions. The prevalence of tenure quotas has thus been reduced by about 50 percent over the past three and a half decades. Moreover, only small and medium-sized institutions reported tenure quotas in the present survey, and such quotas were more prevalent at bachelor’s and master’s than at doctoral institutions (see figure 2).

In opposing tenure quotas, the AAUP’s statement suggested that, rather than introducing tenure quotas, “stricter standards for the awarding of tenure can be developed over the years, with a consequent decrease in the probability of achieving tenure.” The rationale for this option was that similar limitations on the number of tenured faculty members could result without nullifying probation. Since that time, questions about the “ratcheting up” of expectations for tenure have periodically surfaced, and in 1993 the AAUP itself criticized the increasing expectations for tenure as “cruel to members of the faculty, as individuals, and . . . counterproductive for our students’ education.” It added, “Institutions should define their missions clearly and articulate appropriate and reasonable expectations against which faculty will be judged.”

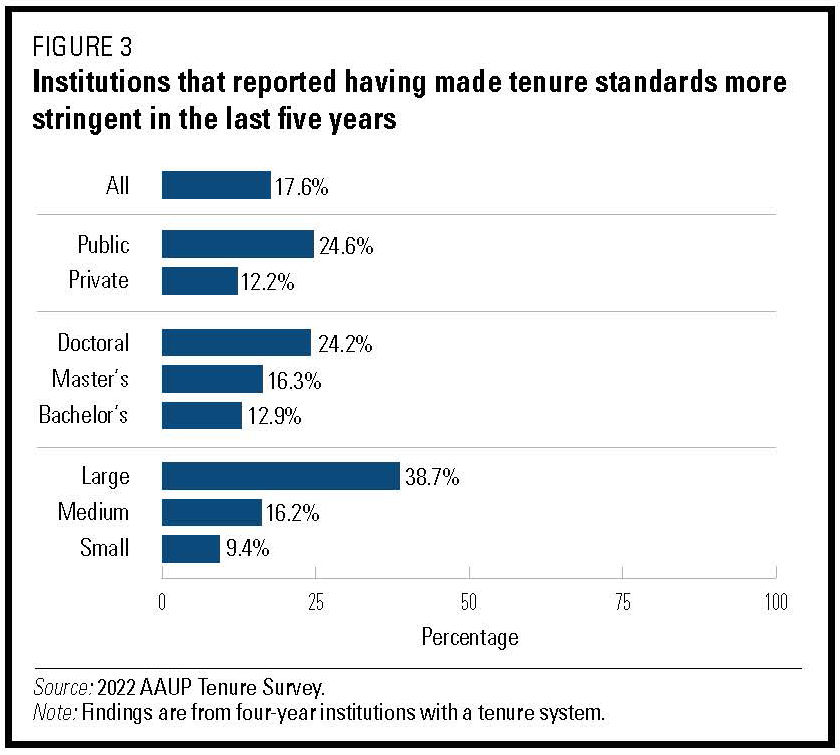

The NSOPF institutional survey regularly asked whether tenure standards had been made “more stringent” during the past five years. In 2004, 13.3 percent of four-year institutions with a tenure system had made their tenure standards more stringent, which is similar to the finding today of 17.6 percent. The current survey shows some differences by institutional type. These are particularly pronounced when we consider size, with 9.4 percent of small institutions, 16.2 percent of medium-sized institutions, and 38.7 percent of large institutions reporting that tenure standards had been made more stringent (see figure 3). That difference is smaller when we compare institutions by Carnegie Classification or by institutional control.

Among institutions that made standards more stringent, 78.9 percent reported that this occurred with respect to research standards, 41.1 percent about teaching standards, 24.2 percent about service standards, and 14.0 percent about other standards. Those who reported that “other” standards had been made more stringent included in their comments examples like community engagement, student success, collegial relations with administration, and mentoring and advising.

Tenure Practices Related to Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

Efforts to improve the institutional climate for diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) can focus on tenure practices and standards. Certainly, it is reasonable to consider, for instance, whether the underrepresentation of women faculty or faculty of color among tenured faculty at an institution may be due to tenure practices, or whether an institution’s stated mission to advance DEI should be reflected in standards for promotion and tenure. Examples of possible types of implicit bias in tenure criteria when it comes to the work of faculty of color or women faculty include requiring research publications in journals that do not focus on research areas in which such scholars may be more often represented, not accounting for systematic differences in how students rate faculty of color or women faculty relative to white male instructors on student course evaluations, and not accounting for mentorship and service obligations that fall disproportionately on faculty of color.

The survey focused on three policy responses regarding tenure and DEI: whether standards for tenure include DEI criteria, whether existing standards for tenure had been reviewed with respect to potential implicit bias during the past five years, and whether faculty serving on promotion and tenure committees had been trained regarding implicit bias during the past five years. While these are certainly not the only ways institutions can address DEI concerns in tenure practices, we identified these three responses as central through interviews with subject matter experts and administrators responsible for faculty professional development. To the best of our knowledge, no previous systematic studies of the prevalence of these responses exist, and thus there are no bases to com- pare our results with previous findings.

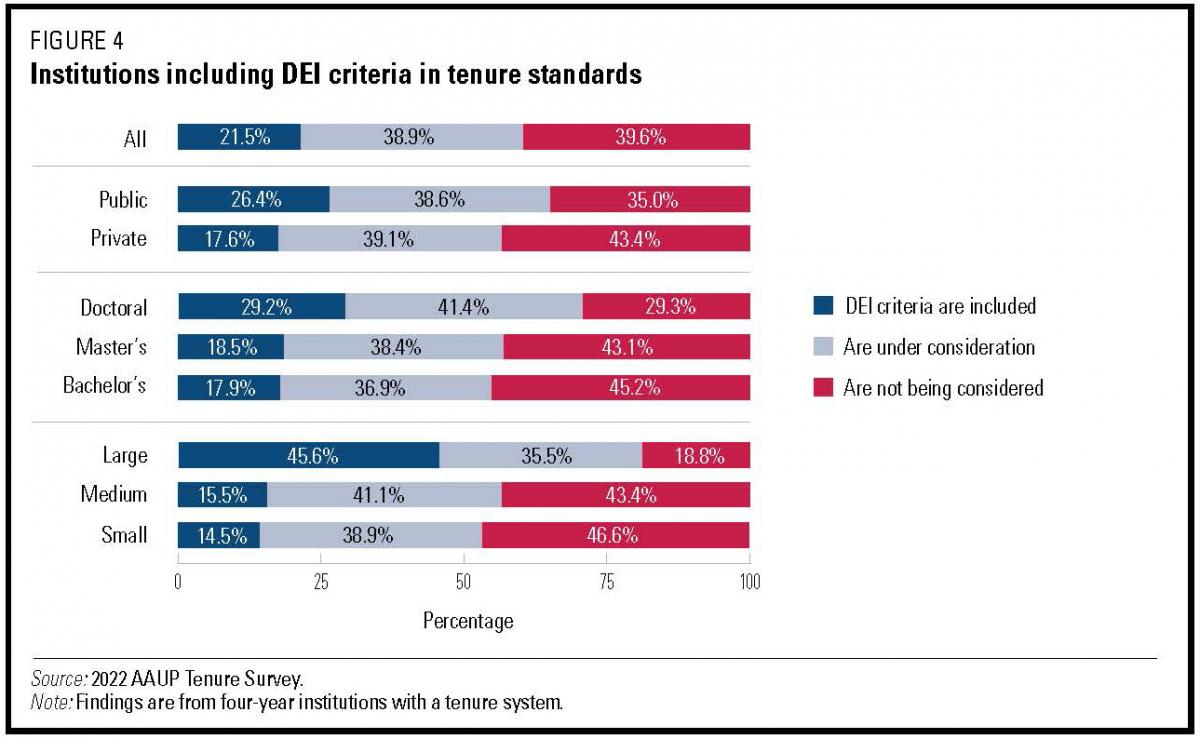

DEI criteria were found in tenure standards at 21.5 percent of institutions. While there were differences among institutions based on Carnegie Classification, with 29.2 percent of doctoral institutions reporting the practice, compared to 18.5 percent and 17.9 percent at master’s and bachelor’s institutions, respectively, the largest difference was by size, with 45.6 percent of large institutions reporting having DEI criteria in tenure standards, compared to 15.5 percent and 14.5 percent at medium-sized and small institutions, respectively.

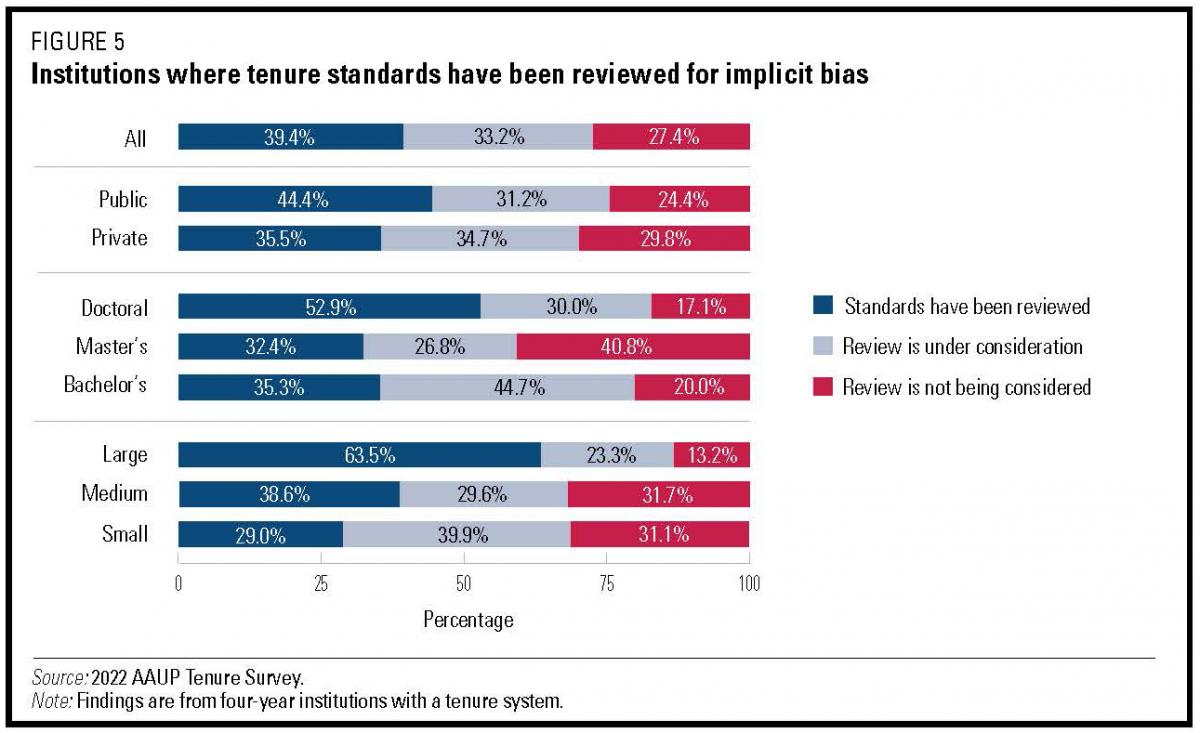

At 39.4 percent of institutions criteria for tenure had been reviewed for implicit bias. Again, there were differences among institutions by Carnegie Classification and size, with a larger difference by size: 63.5 percent of large institutions reported having reviewed standards for implicit bias, compared to 38.6 percent and 29.0 percent of medium-sized and small institutions, respectively.

Respondents who indicated that tenure criteria had been reviewed for implicit bias were asked what actions had been taken as a result of that review. By far the largest number of responses indicated revisions to student course evaluation forms or the elimination of student course evaluations from the tenure process. In addition, respondents reported the broadening of tenure standards, including more explicitly recognizing service obligations that fall more heavily on faculty of color and being more inclusive in scholarly expectations. Regarding student course evaluations, one respondent explained that the institution had added “a mentoring questionnaire so students who may or may not be in [a] faculty member’s classes can be invited to address the value of mentoring.” Two respondents pointed out that they had received NSF ADVANCE grants to support their review of tenure practices from a DEI perspective.

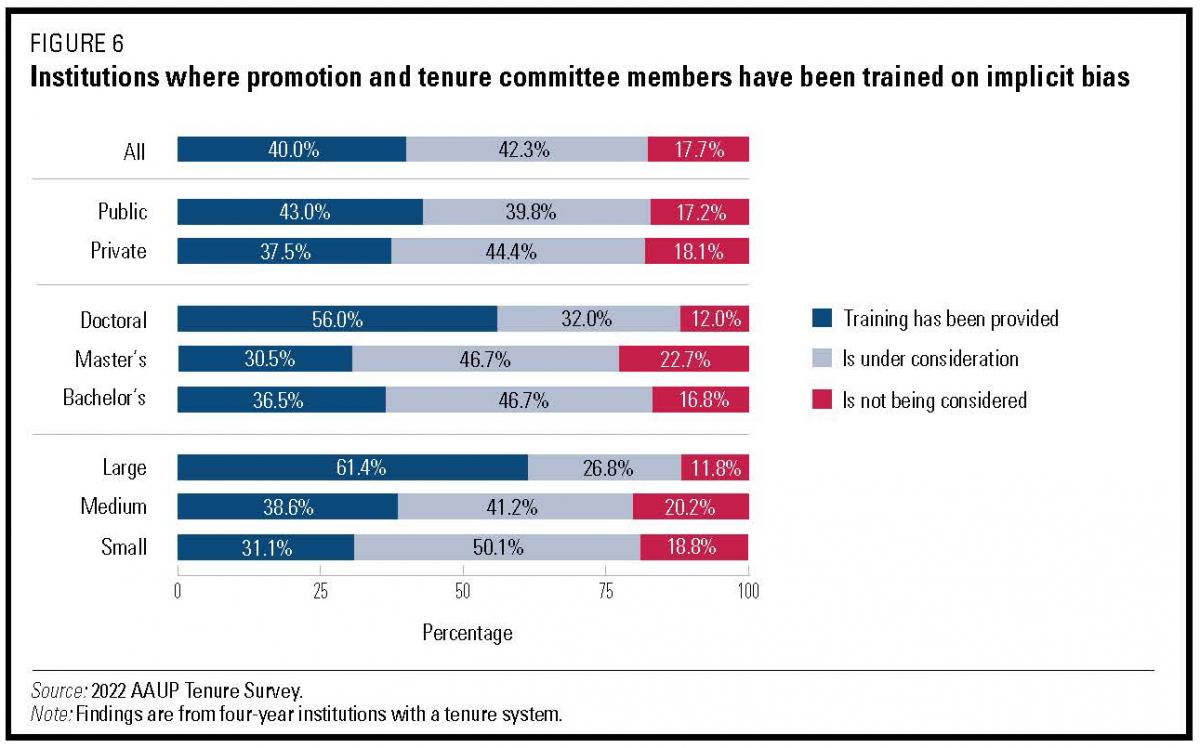

Forty percent of institutions had provided training on implicit bias to members of promotion and tenure committees in the last five years. The difference by size, which was again the most pronounced, was similar to the previous area, with 61.4 percent of large institutions reporting having offered such training, compared to 38.6 percent and 31.1 percent of medium-sized and small institutions, respectively.

Some respondents who sought to advance DEI in the tenure process pointed to challenges that originated from outside of the institution. One respondent observed, “While the university might be able to do a holistic review, there still remains bias in scholarly fields controlling publication.” Another noted, “We are in a state where proposed legislation would greatly restrict our ability to provide training regarding implicit bias.”

For each of the three practices, respondents who indicated that they had not been undertaken at their institution were asked whether the institution was considering undertaking them in the future. Of those who indicated that their institution did not have DEI criteria for tenure, 49.9 percent indicated that it was considering adding them in the future. Similarly, around half (54.8 percent) of respondents who had indicated that no review of tenure criteria for implicit bias had occurred in the last five years indicated that their institution was considering including such reviews in the future. A somewhat higher percentage (70.5 percent) of those who had responded that no training on implicit bias had been provided to promotion and tenure committee members indicated that they were considering it for the future. Figures 4, 5, and 6 combine the responses to the three questions about the presence of DEI-related practices with the questions about whether the institution intends to implement them.

Continuing Threats to Tenure:

Replacement of Tenure Lines

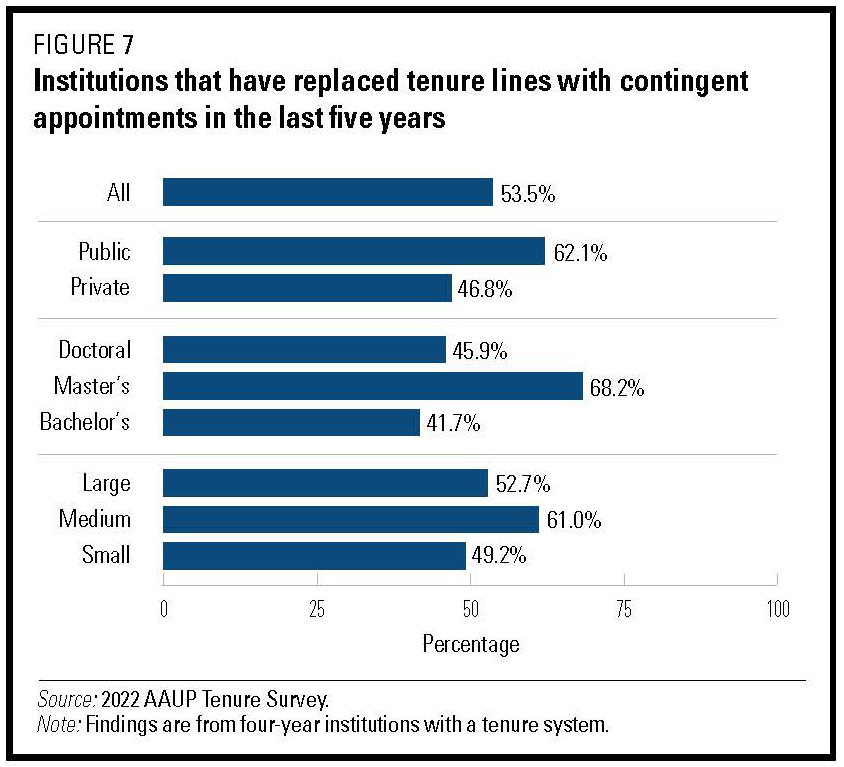

An assessment of the prevalence of tenure practices should also account for ways that institutional actions undermine tenure. For several decades, the AAUP has noted the increase in contingent appointments as a proportion of the academic workforce. According to results prepared by the AAUP research department based on IPEDS data, in 2019, 10.5 percent of appointments were tenure track, 26.5 percent tenured, 20 percent full-time contingent, and 43 percent part-time contingent.

The institutional component of NSOPF reported in 2004 that 17.2 percent of four-year institutions with tenure had replaced tenured with fixed-term positions in the previous five years. As some respondents to the question on this year’s survey noted,the question as formulated describes a specific scenario: a replacement of tenured positions that are vacated by retirement or resignation with fixed-term positions. It does not capture scenarios in which fixed-term positions are added, for example. It also isn’t a measure of how many tenure lines have been replaced but rather only of whether any tenure line has been replaced at the institution. That said, in the present survey 53.5 percent of institutions reported having replaced tenured with fixed-term positions in the last five years, a threefold increase in institutions reporting the practice. Larger proportions of master’s institutions, medium-sized institutions, and public institutions reported replacing tenure lines with contingent positions (see figure 7).

Some respondents noted that they had at the same time converted fixed-term positions to tenure lines; others noted that the conversion had occurred at the request of the department or unit, or as a result of states’ disinvestment in higher education.

Post-tenure Review

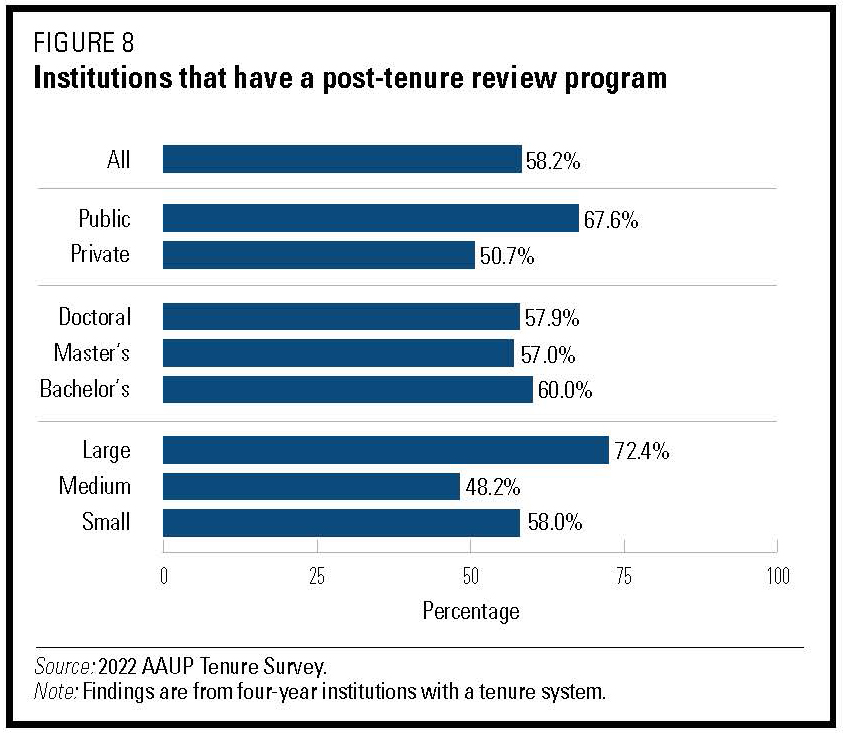

For some time, an additional threat to tenure has been the spread of post-tenure review policies.4 Post-tenure review typically is a comprehensive periodic review of tenured faculty members that is separate from annual reviews. Although the AAUP does not view all post-tenure review policies as at odds with its standards, it considers policies that place the burden of proof on faculty members to demonstrate that they should be retained as inimical to academic freedom and tenure. The present survey asked whether post-tenure review was practiced at the institution and, for those institutions that practiced it, whether the process can result in the termination of appointments. Although the Association’s particular concern in the latter case is whether essential elements of academic due process are provided, the survey could not really explore such details. Nevertheless, since the AAUP’s policies on post-tenure review recommend that such reviews be developmental rather than summative, the possibility that reviews can result in termination raises concerns about their conformance with AAUP standards.

In Cathy Trower’s 2000 study, 46 percent of institutional regulations contained a post-tenure review policy. In the current survey, 58.2 percent of institutions reported having a post-tenure review policy. Thus, while common, post-tenure review policies are hardly universal. Our study found a difference by institutional control, with 67.6 percent of public institutions reporting a post-tenure review program, compared to 50.7 percent of private institutions. This difference may be due to state legislative requirements for post-tenure review or a perceived need by public institutions to conduct such a review in the face of legislative hostility toward tenure. There was no noticeable difference by Carnegie Classification. Large institutions more frequently reported post-tenure review policies than did small and medium-sized ones (see figure 8).

Of institutions that reported having a post-tenure review program, 47.2 percent indicated that the outcome of a review could lead to termination, and thus only about 27 percent of all four-year institutions with a tenure system have post-tenure review programs that can result in termination. Some respondents added that such terminations would be the result of failing to adhere to an improvement plan rather than a direct result of the post-tenure review.

Of institutions that reported having a post-tenure review program, 47.2 percent indicated that the outcome of a review could lead to termination, and thus only about 27 percent of all four-year institutions with a tenure system have post-tenure review programs that can result in termination. Some respondents added that such terminations would be the result of failing to adhere to an improvement plan rather than a direct result of the post-tenure review.

Conclusion

Although it was not the original intent of the 1940 Statement, which proposed that tenure be obtained by virtue of reappointment after the conclusion of the probationary period rather than as a result of a promotion-like review, the tenure system has today become identified with an extensive review process. While the AAUP continues to hold that tenure is acquired due to length of service, which is at times referred to as de facto tenure, it has issued a number of policy statements related to the tenure review process. The present study provides information about the prevalence of tenure practices, some of which relate to the Association’s policy statements.

Among highly prevalent practices that conform with the Association’s standards, the presence of a probationary period of fixed length that generally results in a tenure decision in the sixth year dates to the 1940 Statement. Permitting probationary faculty members to stop the tenure clock for reasons of childbearing or child rearing, which the AAUP adopted as a policy recommendation more recently, is also a common practice at this point. Conversely, tenure quotas and post-tenure review programs that can result in termination of appointment, both of which are at odds with AAUP policies, are relatively rare. In contrast, the practice of replacing tenure lines with contingent appointments, one entirely at odds with the Association’s standards, has markedly increased in the past two decades.

The present study also provides information about tenure practices related to diversity, equity, and inclusion. Press reports of such efforts at individual institutions have at times focused on opposition to them by faculty members, outside organizations, or state legislatures. It should be noted that AAUP policy generally does not provide substantive grounds to oppose tenure practices and standards that promote DEI. For instance, AAUP policy does not support claims that DEI criteria for promotion and tenure are political litmus tests or somehow akin to loyalty oaths. Nevertheless, the focus on opposition to such activities may have caused them to be viewed as “controversial,” which may help explain the relatively high percentage of institutions that are not considering undertaking them. The fact that several respondents reported changes to the format or use of student evaluations points to a need to consider in more detail how institutional practices in this area are changing.

While tenure is regularly under attack, by both institutional practice and legislation, it continues to serve as the bulwark in the defense of academic freedom. As such, it is essential to study practices related to tenure systematically and on a regular basis, as this study has done.

Appendix: Methodology

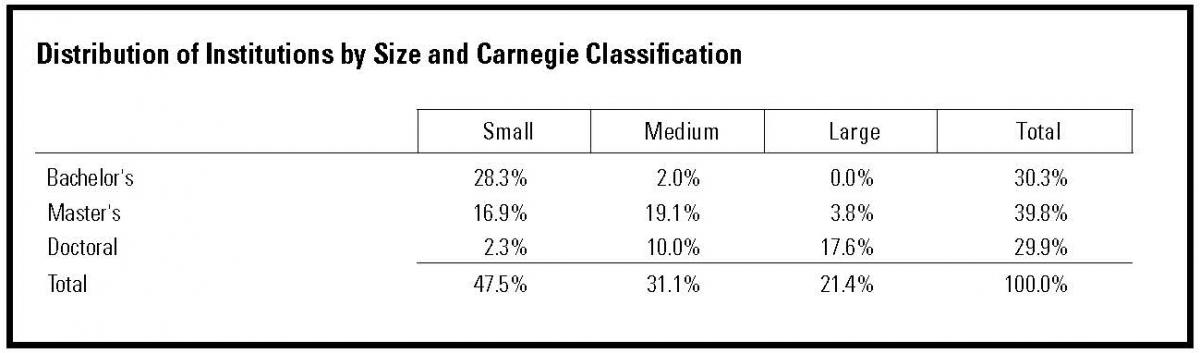

As mentioned above, this study is intended to be generalizable to a population of some 1,200 four-year institutions that have a tenure system and a Basic Carnegie Classification of being a doctoral, master’s, or bachelor’s institution. Within that population, 30.3 percent are bachelor’s institutions, 39.8 percent master’s institutions, and 29.9 percent doctoral institutions; and 47.5 percent are small institutions, 31.1 percent are medium-sized, and 21.4 percent are large. The above table contains information about the distribution of four-year institutions with a tenure system by size and Carnegie Classification.

The questionnaire was administered to a stratified random sample of 515 chief academic officers and had a response rate of 52.8 percent, using the American Association for Public Opinion Research definition of response rate (RR2). In a few instances, the survey was completed by another academic affairs administrator (such as an associate provost), who was designated because of their responsibility for the promotion and tenure process.

We stratified the population by Carnegie Classification and size into five strata and drew disproportionate, random samples from each stratum, oversampling small strata and undersampling large ones. The five strata were bachelor’s institutions, small master’s institutions, medium-sized and large master’s institutions, small and medium-sized doctoral institutions, and large doctoral institutions. The purpose of these sampling choices was to ensure adequate numbers of institutions within each stratum for further analysis.

In order to increase participation, the AAUP sought the endorsement of national associations that are members of the Washington Higher Education Secretariat. The endorsements were listed on correspondence inviting participation. The following associations endorsed the survey: the American Council on Education, the American Association of Colleges and Universities, the Association of Research Libraries, the College and University Professional Association for Human Resources, the Council of Independent Colleges, the Council on Social Work Education, the Educational Testing Service, and the Phi Beta Kappa Society. We would like to thank these organizations for their support.

Two responses were excluded from the final analysis because they indicated that the institution does not have a tenure system. Nineteen responses were breakoffs that had extensive item nonresponse and were excluded as well. To improve the accuracy of the estimates, we weighted the results of the study with design weights to account for the disproportionate selection across the different strata and weights to account for unit nonresponse.

Estimates of proportions in the population made on the basis of a sample have a margin of sampling error. That margin depends on the sampling design (the “design effect”), the size of the sample, the finite population correction, and the estimated proportion itself. With 271 respondents in this stratified sample, the margin of error is about +/− 5.4 points when the proportion reported is 50 percent, which is the proportion at which the margin of error is largest for a given sample size. Thus, for example, the estimate that 50.5 percent of institutions allow faculty members to stop the tenure clock for elder care has a 95 percent confidence interval of 45.1 percent to 55.9 percent. The margin of error is larger when proportions are reported for smaller subpopulations (such as by Carnegie Classification, size, and so forth). ■

HANS-JOERG TIEDE

Director of Research, AAUP

1. Cathy Trower, ed., Policies on Faculty Appointment: Standard Practices and Unusual Arrangements (Boston: Anker, 2000).

2. Hans-Joerg Tiede, “Policies on Academic Freedom, Dismissal for Cause, Financial Exigency, and Program Discontinuance,” Bulletin of the American Association of University Professors (supplement to Academe), 2020: 50– 65.

3. See, for example, Colleen F. Manchester, Lisa M. Leslie, and Amit Kramer, “Is the Clock Still Ticking? An Evaluation of the Consequences of Stopping the Tenure Clock,” ILR Review 66, no. 1 (January 2013): 3–31.

4. See, for example, the recent investigation of the University of Georgia system for an extended discussion of the threat posed by the systemwide introduction of changes to a post-tenure program.