- About

- Programs

- Issues

- Academic Freedom

- Political Attacks on Higher Education

- Resources on Collective Bargaining

- Shared Governance

- Campus Protests

- Faculty Compensation

- Racial Justice

- Diversity in Higher Ed

- Financial Crisis

- Privatization and OPMs

- Contingent Faculty Positions

- Tenure

- Workplace Issues

- Gender and Sexuality in Higher Ed

- Targeted Harassment

- Intellectual Property & Copyright

- Civility

- The Family and Medical Leave Act

- Pregnancy in the Academy

- Publications

- Data

- News

- Membership

- Chapters

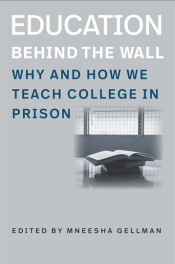

Reports on Higher Education in Prison

Education Behind the Wall: Why and How We Teach College in Prison. Mneesha Gellman, ed. Brandeis University Press, 2022.

Higher education in prison is a growth industry, and the opportunity to work in these programs is becoming a more widely available option for college and university faculty members. While a few institutions—notably Mount Tamalpais College, which began in 1996 at California’s San Quentin prison as the Prison University Project—have a long history with such programs, most of those currently flourishing began in the twenty-first century. Private colleges and universities spearheaded the movement and still lead the field, but a look at the website for the Alliance for Higher Education in Prison reveals the increasingly widespread and diverse presence of higher education inside the walls of US carceral institutions. The long-overdue removal of a ban on Pell Grants for incarcerated individuals has helped fuel this increase, though universities had begun to create prison programs before this momentous change. While public universities still lag decidedly behind private institutions in providing for-credit programs in prisons, there is no doubt that we are in a moment of expansion, innovation, and opportunity for this subsector of higher education.

In the collection Education behind the Wall: Why and How We Teach College in Prison, editor Mneesha Gellman and her contributors tell powerful and instructive stories about how higher education institutions and individual faculty members can stumble their way into positive contributions to the lives of the incarcerated. And “stumble” often is the way, as the obstacles facing both institutions and individuals force even the most experienced educators to learn by trial and error. All but one of the chapters in the collection are written by people affiliated with the Emerson Prison Initiative (EPI), which has a program in the Massachusetts Correctional Institution at Concord, a medium-security facility for men. But the experiences and the lessons are evocative of what goes on at similar prison programs across the country. Readers of Academe may be familiar with such programs, from their own experience or from some of the pathbreaking reporting of recent decades. The PBS documentary Prison Behind Bars is one great introduction, as is Daniel Karpowitz’s study College in Prison: Reading in an Age of Mass Incarceration. Gellman’s collection makes a significant contribution to this body of work and concludes with an appendix that provides numerous accounts of American carceral culture as well as histories of college-in-prison programs.

Gellman wants readers to see this book as more than a manual, and it is, but it is first and foremost a useful and brass-tacks guide to how a prison program works. From the individual perspectives of various contributors, we learn about the logistics of literature and writing courses, math instruction, digital issues, research challenges, day-to-day routines, senior theses, and more. But, as Gellman writes in her introduction, in addition to asking how, the book also asks why and who. Formally, the book is a series of testimonials—microhistories that express the motivations, feelings, and political concerns of the various participants. What emerges is a kind of group memoir recounting individual experiences, a practical manifesto, and a philosophical intervention into America’s carceral culture. In a nonprogrammatic way, Education behind the Wall offers a set of claims about authority in relation to prison education and in relation to our historical moment.

One of the more compelling testimonials is Elizabeth B. Langan’s chapter, “Surviving the School-to-Prison Pipeline,” which demonstrates both the depressing realities of US carceral culture and the positive energy that prison education programs can generate. As a veteran of college-level teaching who had recently retired from teaching middle school in Boston when she began to work in the EPI, Langan draws connections across different parts of her teaching career. The desire to achieve “containment and control” that she notices at the correctional facility seems consistent with her experiences teaching in Boston’s “lower track” schools, and she fleshes out those connections throughout the chapter. Discussing the lived reality of the pipeline in her title, whether one considers it to be a “school-to-prison” or “cradle-to-prison” pathway, the chapter takes us outside of the prison in order to think about what it means to be housed there; in some ways, her account works like the extraordinary documentary film A Prison in Twelve Landscapes, which never goes into a prison but explores the complementary landscapes that exist symbiotically with prisons. Langan’s prison students remind her of the middle schoolers she had taught, and she narrates the stories of a few specific students from that earlier part of her career. “Stunned by trauma,” “entering the pipeline,” these boys of her memories now seem much like the grown men in front of her, except that these grown men choose to change, as much as they can: “By definition, students in a college-in-prison program will have already decided that the end of the pipeline, for them, will not be a dead end.” Such self-transformation is a central theme of this book and the broader movement to which it belongs. Langan conveys the potential impact of higher education on the lives of incarcerated men, who are at a stage of their lives when they are ready to assert agency and move forward. Many of the essays speak of the exceptional energy and openness that incarcerated students bring to their classwork.

A keyword for the collection and a concept that many of the essays wrestle with is authority and the number of forms of it at play in this subsector of higher education. Stephen Shane’s contribution, “Finding Their Voices: Student Experience as Authoritative Framework for Genre-Based Writing,” combines practical advice with a philosophical approach to the multiple authorities present in and around the college-in-prison setting. Shane outlines a writing course that proceeds through four assignments based on genres: memoir, profile, academic research essay, and open letter. Shane wants to decenter his own authority in the classroom and encourage his students to seize their own sense of control and thereby feel empowered. While this kind of advice works in a traditional, on-campus classroom as well, the nature of authority in a site of incarceration raises the stakes for understanding how power works. Like many other contributions to Education Behind the Wall, Shane’s chapter voices an idealistic sense of an inversion of power roles in the will to flip the script about where authority might ultimately reside. It concludes with his own version of the final assignment for the course: an open letter. Addressing his students, he writes, “Something that I hope you remember is that Emerson College and EPI are fortunate to have you as part of our community. Without your voice, your perspectives, your stories, we are not whole.” For readers of this essay collection as much as for his incarcerated students, this hopeful valediction expresses some of the almost utopian energies of the movement, which rests on a radical reimagining of authority.

The other contributors to this book each tackle an aspect of higher education in prison, often emphasizing a philosophical point within narratives of practical advice. Kimberly McLarin and Wendy W. Walters draw on James Baldwin’s idea of “the report that only the poets can make” to anchor their discussion of what literature courses—and, by extension, the arts and sciences more broadly—can bring to incarcerated students. Intriguingly, in an era when university administrators and state legislators are emphasizing a utilitarian and careerist approach to education, and when humanities offerings are being aggressively winnowed, many prison programs have chosen specifically to endorse a liberal arts approach. McLarin and Walters draw on Audre Lorde’s manifesto “Poetry Is Not a Luxury” to assert that the incarcerated can be uniquely served by the liberal arts: “Poetry is vital to those whose lives have been constrained by confinement and dehumanization—but who are trying to transcend those constraints.” Alexander X, the only incarcerated contributor to the collection, writes in “Learning to Live” about how his student experience changed many of his worldviews and reversed his sense of the purpose of learning. Gradually coming to an acceptance of the idea that “you are not your crime,” Alexander concludes, “I went from the escapism of living to learn to the optimism of learning to live.” Sally Moran Davidson writes in “Teaching Quantitative Reasoning in Prison” about how her approach evolved as she confronted particular challenges. With “intuitions, graphs, and formulas” as shorthand for her method, Davidson tells of how she got to the point where her students “are able to see shifting curves everywhere” as they assimilate concepts from the match course into their ways of living in the prison. This chapter captures how educators must and do adapt to the dynamics of incarceration, including returning to an almost tech-free classroom and class management. The theme runs throughout the book, but it is addressed directly in Christina E. Dent’s “Paywalls, Firewall, Prison Walls: Bridging the Digital Divide within the Prison Education System.” Most prison classrooms have no digital access, and the students have tightly controlled access to the internet. Imagine teaching without your laptop or PowerPoint presentations, reading handwritten assignments, and having no ability to communicate with your students between class sessions—this is a digital divide of a different magnitude. A librarian, Dent recounts the journey she made toward workable research systems for her students, narrating the specific things she did to “create mechanisms to circumvent the digital divide in order to grant EPI students equitable access to research and information.” Here, the pursuit of equitable access drives Dent and her staff to devise creative and practical work-arounds to deliver a high-quality education.

Several essays serve more heavily as how-to guides, emphasizing advice that offers readers particulars of what teaching in prison requires and feels like. Shelly Tenenbaum’s “Days in the Life of a College-in-Prison Professor” dissects the entry process, the classroom procedures, the emotional challenges, and commencement. She shows how this is a “two-way process,” changing the educators as well as the students. In “The Logistics of Preparing to Teach Inside,” Cara Moyer-Duncan tells the history of the Emerson Prison Initiative, covering the topics of program design, course selection, faculty orientation, syllabus preparation, censorship, guidelines for getting prison approval for media use, student assessment, course evaluations, and last-minute logistics. These are all topics most college educators already know about, but they take on markedly different shapes in the prison education context. Justin McDevitt and A. D. Seroczynski, who work in Indiana for the Moreau College Initiative, a joint project of Holy Cross College and Notre Dame University, tackle two challenges in “One Foot In, One Foot Out: Senior Theses and Remote Internships in the Prison Space.” The Moreau Initiative found ingenious adjustments for reshaping these traditional end-of-college experiences for incarcerated students.

Faculty governance and academic freedom take on different meanings in prison education. With respect to who is in charge and what can be taught, teaching staff have to work within the constraints of the department of corrections. As much as one would like to believe that “once that door closes you are now a student at X College,” there are always accommodations made to the prison before the door closes, and not everyone agrees that prison programs do much to change the power structures. It is possible to imagine that we are aiding and abetting the prison-industrial complex. But in the testimonies in this book and in my personal experience and the experiences of many prison educators I know, negotiating with and at times accommodating corrections authorities doesn’t eliminate the liberatory and even revolutionary power of prison education. Mneesha Gellman’s collection of essays attests to this reality, and if you want more convincing, there are programs out there looking for your participation.

William Kerwin is associate professor of English at the University of Missouri and the founder of the Missouri Prison Education Program. His email address is [email protected].