- About

- Programs

- Issues

- Academic Freedom

- Political Attacks on Higher Education

- Resources on Collective Bargaining

- Shared Governance

- Campus Protests

- Faculty Compensation

- Racial Justice

- Diversity in Higher Ed

- Financial Crisis

- Privatization and OPMs

- Contingent Faculty Positions

- Tenure

- Workplace Issues

- Gender and Sexuality in Higher Ed

- Targeted Harassment

- Intellectual Property & Copyright

- Civility

- The Family and Medical Leave Act

- Pregnancy in the Academy

- Publications

- Data

- News

- Membership

- Chapters

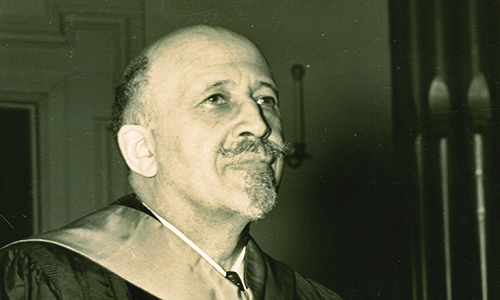

Toward the Cooperative University: W. E. B. Du Bois’s Membership in the AAUP

Reflections on a radical vision for higher education.

In 1937, at the tender age of sixty-nine, W. E. B. Du Bois paid a $4 membership fee and joined the American Association of University Professors. Du Bois was several years into his second stint as a professor of sociology at Atlanta University. He had previously taught in Atlanta from 1897 to 1910 before moving to Harlem, where he helped to establish the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and edited its journal, the Crisis, for twenty-three years. By the mid-1930s, when the United States was in the throes of the Great Depression, Du Bois had become too radical for the liberal reformists at the NAACP and had rejoined the ranks of the professoriate. Over the course of another decade, he lectured on Marx, offered pro bono evening classes for Black working people, and honed an altogether new vision of the university.

Du Bois’s membership in the AAUP was short-lived. He resigned in 1945, ostensibly in protest of the organization’s practice of holding meetings in segregated hotels.1 But his differences with the AAUP ran far deeper than concerns over equal access. This was a period in which Du Bois had grown disillusioned with the modern university, an institution that had been forged in empire and was set up, in his view, to reproduce class divisions and competitive animosities. He had come to fear that the conventional model, which he saw as enmeshed in capitalism and liberal property relations, could not deliver substantive racial progress. And he had begun to experiment with new ideas about a more cooperative university that could shape and sustain a more cooperative world. The AAUP, focused as it was on establishing professional standards and protecting academic freedom, simply did not challenge the political economy or governance structure of the university in ways that might have aligned with Du Bois’s increasingly radical vision.

In this speculative essay, I read Du Bois’s midcentury theory of the university in tandem with recent scholarship on the university’s corporate legal structure. I suggest that we might think of Du Bois’s later work in terms of an effort to reconstitute the university as a cooperative, and as part of a broader cooperative movement within American society. Du Bois, for his part, never really got these ideas off the ground. By the late 1940s, he had been pushed out of academia, and over the next decade and a half, until his emigration to Ghana in 1961 and his death soon after in 1963, his work was increasingly stifled under the weight of “Black Scare/Red Scare” repression.2 But his story is something of a cautionary tale, one that remains edifying well beyond its historical context. To be sure, today’s AAUP is not Du Bois’s. The organization has since embraced the labor movement and now facilitates critical work to reshape the political economy of higher education. Still, a creative recovery of Du Bois’s cooperative agenda might further expand the horizons of campus organizing in our moment.

Intellectual History

Several considerations led Du Bois to leave his position at the NAACP and return to the professoriate in 1933. Not least among them was an evolving vision for how educational institutions, and the university in particular, fit into the struggle to build a more just and sustainable world. Du Bois had spent decades developing a critical theory of what he called the “white world,” what we might identify broadly as the age of European empire. This is the prevailing world order that we all know and experience, conscripted as we are into its epistemic and material workings. And for Du Bois, this world’s most widely celebrated ideals and practices—essentially private property ownership and competitive market individualism—are inextricably tied to the endurance of white racial domination, a notion of whiteness, as he once put it, as “ownership of the earth forever and ever.”3

Du Bois always maintained that capitalism and liberalism, what he regarded as the “civilizational” contributions of European modernity, were born in slavery and anti-Black racism. And by the 1930s he had come to believe that they could never be fully severed from these roots, never redeemed in a way that would fundamentally unsettle white world domination. If capital accumulation by its nature requires exploitation and expropriation, then for Du Bois these practices were destined to remain racially coded. If a rights-based liberalism encourages competitive market behavior, then this, too, was poised to reproduce racial animosities and divisions. Du Bois had come to see that, while these organizational principles may not always present themselves in overtly racist ways—the whole civil rights tradition, for example, can be understood as a good-faith effort to expand the protection of individual rights and liberties—they tend simply to reinforce and legitimize ownership claims over accumulated wealth, power, and privilege.

Elsewhere I have suggested that we might think of Du Bois’s later disillusionment with the white world in terms of a “critique of the competitive society.”4 Earlier in his career, he was more ambivalent about some of the theoretical contributions of the white world, especially liberalism. But on the heels of the Great War and in the midst of the Great Depression, by the time he left the NAACP and returned to Atlanta University, he had begun to challenge the notion that “social reform” meant “primarily the opening of doors to black men, so that they might run the race of life in equal competition with the white.”5 Familiar liberal tropes of equal opportunity, fairness, and meritocracy may appear reasonable and perfectly compatible with a movement beyond legacies of racist oppression. But they amount to a kind of ideological distortion, obscuring our perception of an underlying reality. Our celebration of a competitive liberal paradigm provides convenient cover for a world in which unequal outcomes are proof of concept, a world in which loss, poverty, and depressed social standing are not systemic problems to be overcome through collective action but assets to the system itself, essential means by which we are compelled to work, consume, and innovate. And the key for Du Bois is that the core principles of this competitive society—again, on their surface not inherently racist—were co-constitutive with intense racial stratification. And this competitive society invites, as it were, traces of this racist past into the present and future, all but ensuring that market actors will continue to leverage racial and other ascriptive differences in the ongoing struggle for competitive positioning.

This disillusionment with liberalism led Du Bois to rethink his philosophy of higher education. Du Bois, of course, is well known for his turn-of-the-century debate with Booker T. Washington over the relative merits of vocational training versus liberal arts education.6 Early on, he established himself as a defender of the liberal arts. In that commitment, he never wavered. But as his thinking about liberal democracy evolved into the 1930s, so too did his sense of what it means to educate a democratic citizenry. How, after all, are we to understand the work of preparing a free or “liberated” people for self-government—the very nature and purpose of liberal education? If the idea is not simply to give students the knowledge and tools to compete as free and independent citizens, then what follows? Does a properly democratic education require something like an exercise in Du Bois’s later concept of “abolition-democracy”—a simultaneous tearing down of one world and building up of another?7 And what would that entail?

This was the context in which Du Bois introduced what has come to be known as the “Black University concept.”8 This notion would ultimately inspire an ambitious political movement during the heyday of Black studies activism and Third World liberation in the 1960s.9 The basic idea was that where schools in the European tradition had been set up to serve colonial projects and reproduce inequality, the Black University had to establish itself as an altogether different sort of institution, a hub of inquiry and research dedicated entirely to a new kind of world-making agenda. This meant new curricula and new pedagogies, anchored in values and principles drawn from Black history and experience and imagination. And it meant building community and facilitating a more cooperative and sustainable mobilization of resources. Clearly no established Black college or university could fit the bill. To paraphrase Joy James, if one teaches at a state school, one works for the state; if one teaches at a private school, one works for capital.10 In this regard, established Black institutions of higher education, what we today call historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs), are no different from their predominantly white counterparts. As Du Bois once lamented, “Negroes are receiving their education from white capitalism and they are trying to follow in its worn footsteps.” What was needed, he stressed, was a far more “unusual course of education and several successful experiments [in] co-operation.”11 The Black University concept, as envisioned by Du Bois, was then and remains now a kind of speculative ideal, something of an open-ended inquiry into the kinds of educational institutions that might be culled from the prophetic wisdom of the Black world. Such an institution, Du Bois hoped, could help to move humanity beyond cycles of race- and class-based divisiveness, beyond a competitive world torn between winners and losers.

The Corporate University

Remarkably, if regrettably, Du Bois’s concerns have aged well. When we fret today over the “neoliberal” or “corporatized” university, we worry about an institution that has become more fully vested in the competitive society. We lament that education has become commodified, reduced to a marketable private good over which students qua consumers compete. We brace ourselves as university administrators qua managers announce round after round of austerity, forcing those of us who teach and research to compete ever more fiercely over jobs and funding. We pretend we’re only joking when we cry out that our model institutions, those well-endowed universities that are so lauded as industry leaders, have become giant hedge funds that run schools on the side for tax purposes. The university as we know it is fundamentally a gate-keeping institution; both epistemically and materially, as ideology and as industry, it enshrines the commitments to private property ownership and competitive market individualism that Du Bois identified as the defining features of the white world. And even where universities may facilitate some critical analysis of these commitments—say, in selected course offerings or certain research initiatives—such is never the dominant work of the university, nor does it represent any real resistance to the education industrial complex. We still pile on student debt. We still jockey over “stackable credentials.” Our institutions still compete over new revenue streams and police their campuses and gentrify surrounding neighborhoods as the property owners they are. These tendencies continue to spiral beyond our control, as the new modalities of racial division and inequality.

Timothy V. Kaufman-Osborn has contended that we need a more sophisticated analysis of the “corporate” nature of higher education. It is worth spending a moment on his argument before returning to Du Bois. “No matter how vociferously critics bemoan the ‘corporatization’ of America’s colleges and universities,” Kaufman-Osborn says, “the fact remains that they are almost always organized in the legal form that is a corporation.”12 To be sure, it is nearly impossible to imagine any college or university at any time or place, insofar as it is formally organized at all, that is not organized as some sort of corporate body. Etymologically, both college and university evoke notions of “corporation, society,” “community, guild,” an “association” of masters and scholars.13 The problem, Kaufman-Osborn argues, is not the corporate form as such. The problem is that within the legal architecture of the United States, at least since the Supreme Court decided Trustees of Dartmouth College v. Woodward in 1819, nearly all formally chartered colleges and universities have been considered a particular kind of corporation, a “property corporation” rather than a “member corporation.” We may still romanticize the college or university as some form of the latter, a “self-governing republic of scholars,” as James Cattell and the AAUP’s first secretary, Arthur Lovejoy, once put it.14 But in reality, absentee boards of regents, visitors, overseers, or trustees are by law granted unilateral governing authority over the institution, including its faculty, and are tasked with protecting the will of founders and donors in perpetuity—protecting, in other words, the asset value of the institution as property. Over time, this legal architecture has become more fully integrated into the political economy of the nation and world, to the point where this corporate form seems to have reached its apotheosis. At a neoliberal moment in which notions of human capital and entrepreneurialism predominate, in which the public good has been more or less entirely refashioned as the facilitation of private interest—in other words, in a more fully consolidated competitive society—it has come to appear all but inevitable that the “task of governing boards is not to ensure fulfilment of ends that can be distinguished as specifically educational but to structure any given college or university’s mode of implication within late capitalism.”15

The AAUP, for its part, never really sought to challenge the university’s legal design. In his history of its early years, Hans-Joerg Tiede recounts how the AAUP briefly considered but pivoted away from these matters, opting to focus instead on the establishment of professional standards and the protection of academic freedom.16 Clyde Barrow has referred to this as the AAUP’s “accommodationist strategy.”17 Its early leadership, he argues, embraced a liberal framework of “competitive pressures,” assuming that “market structures would be relied upon to provide the pressure toward accommodating AAUP demands, rather than any national boycott, strike, or political tactics.”18 This quickly became an influential approach. Laura Weinrib has argued, for example, that in the 1920s the AAUP contributed to the American Civil Liberties Union’s turn from the labor movement and a more radical critique of the legal architecture of the class struggle to a narrower liberal emphasis on protection of “autonomy and individual rights.”19 Kaufman-Osborn has gone so far as to say that because the AAUP “failed to call into question the academy’s essential constitution of rule,” the organization “has done more to reinforce than to challenge” what we now decry as the “corporate takeover” of our colleges and universities.20

Du Bois's AAUP Membership

With the foregoing as a lens of analysis, we can develop a reading of Du Bois’s brief membership in the AAUP. He was invited to join in 1935, did so in 1937, and in 1938 helped to charter a new chapter at Atlanta University. There is ample evidence to suggest that his thinking, at least for a period, aligned with the main thrust of the organization. In “general information” materials sent to him at the time, the AAUP underscored its aims of establishing within academia a “collective professional self-consciousness,” a “more effective cooperation among teachers and investigators,” and “standards and ideals of the profession.”21 In the first year of the Atlanta chapter’s existence, Du Bois gave a dinner talk on “tenure and titles” and appears to have used another meeting as an occasion to lift himself up as a professional exemplar that his colleagues might emulate.22 “We had a meeting of the AAUP last week in my office,” he recounted in correspondence with the sociologist Ira De Augustine Reid. “They wanted to know something about research projects which I had on hand. I piled up the stuff until they gasped and were properly impressed. I hope it will make some of them go to work.”23 Though we can debate what exactly professionalization might have meant for Du Bois in the context of his evolving vision of the “field and function of the Negro college,” some notion of raising faculty standards seems to have been a persistent theme for him—and an emphasis on faculty standards has been perhaps the signal import of the AAUP’s presence on HBCU campuses over the years, as they have fought to meet requirements imposed by regional accreditation bodies.

Du Bois also participated in chapter meetings on “the role of the faculty in the administration of a college.”24 Though we have no record of what was discussed in these meetings, all indications are that Du Bois embraced, as the AAUP has more or less since its founding, the governance model of the property corporation. Because of his stature and platform, and his immense gift for persuasive speech and writing, Du Bois had far more influence over presidents and governing boards than did other rank-and-file professors. At times, he appears to have relished his status as a “kingmaker” at his alma mater, Fisk University.25 But throughout the 1930s and early 1940s, one finds a Du Bois broadly accepting of the premise, articulated in the AAUP’s 1915 Declaration of Principles on Academic Freedom and Academic Tenure, that “American institutions of learning are usually controlled by boards of trustees as the ultimate repositories of power.”

Then, in 1944, with no forewarning or due process, Du Bois was summarily dismissed from Atlanta University. More precisely, he was involuntarily retired by the board of trustees at the behest of university president Rufus Clement. As one might have predicted, Clement had come to perceive Du Bois as a threat to his authority. One report suggested that “relations between him and Dr. Du Bois had reached the place where it was the case of him or Dr. Du Bois running the university.”26 Over the course of the nearly yearlong dustup, allegations were levied on both sides: Du Bois was said to have been “difficult to work with” and uncompromising in the classroom; the university was said to have violated tenure rules and circumvented procedures. Notably, there is no record that the AAUP was consulted or involved in any way. Du Bois’s friends, colleagues, and students lobbied on his behalf, while Du Bois lamented the cold, hard reality: “how difficult it is for one in my position to have no avenue of protest or complaint.”27 And he was right. Atlanta University, chartered in the state of Georgia on the model of the property corporation, granted unilateral governing authority to its trustees. And he had burned his bridges. By the mid-1940s, Du Bois had published work that deeply unsettled white philanthropists, promoted free evening classes for Black working people as part of a “people’s college” initiative, and begun work on a research project that would have exposed government underinvestment in Black land-grant colleges and universities.28 In the minds of those entrusted with protecting the value and competitiveness of Atlanta University under Jim Crow, Du Bois had become a labor investment that was simply too risky, too costly.

We ought to be careful not to overplay this episode for dramatic effect. But regardless of whether Du Bois’s dismissal resulted in some kind of conversion experience in his thinking about the university as an organized institution, it can help to shape how we interpret his subsequent decision to leave the AAUP. As I noted at the outset, Du Bois resigned from the AAUP in 1945 ostensibly in protest of the organization’s practice of holding meetings in segregated hotels. And at that point Du Bois was seventy-seven years old and out of academia, back in New York as a research director at the NAACP. Whatever acute factors may have contributed to his decision to leave the AAUP, we ought to recognize that the most distinctive and normative aspects of his thinking about higher education in this period were ultimately incompatible with the AAUP’s approach to university reform. And the implicit tensions between Du Bois and the AAUP may help to inform how we approach faculty organizing work in our own time.

A Cooperative University

Faculty organizing in this respect turns on how we understand the import of cooperation, both as principle and as organizational structure. So far, I have focused on the diagnostic side of Du Bois’s critical theory. I have suggested that his thinking about the university was part of an evolving critique of the competitive society. On a more prescriptive register, as one would expect, Du Bois was a spirited proponent of cooperation. He had long supported Black worker and consumer cooperatives. And we might think of his post-1930 vision of the Black University in terms of a movement to build educational cooperatives.

The concept of the Black University began with the idea that the existing world order was unjust and unsustainable, and this assessment went well beyond any simple concern about discriminatory or unfair application of principles. According to Du Bois, we needed a different set of commitments, and for him cooperation was to be an orienting principle in the pursuit of a new world. The university, for its part, had to promote cooperation in its curriculum, its pedagogy, its research initiatives. But even more important, as an institution it had to manifest an “experiment in co-operation.” It had to be, in its material workings, an “example of intelligent cooperation.”29 The AAUP had made only a half-step in this direction in its appeal to what we now call “shared governance.” In materials sent to Du Bois in the 1930s, under the bolded heading of “cooperation,” the AAUP stated that it “has recognized from its foundation the importance of cooperation with organizations of college and university administrative officers in dealing with problems of common interest.” But we have seen how this worked out for Du Bois. In our own time, we are seeing how it works out for West Virginians and Floridians and Texans and everyone else at the mercy of autocratic governing boards. The appeal to shared governance as mere convention, as Barrow says in his analysis of the AAUP’s strategy, is “highly contingent on the good will and cooperation of benevolent university administrations—who themselves legally [remain] agents of the trustees.”30 Moreover, beyond the internal governance of the institution, trustees who, as fiduciaries, are legally bound to protect the asset value of the university as property simply cannot preside over an institution that nurtures cooperative relationships with the outside world.

But what if colleges and universities were rechartered, reincorporated as cooperatives rather than property corporations? What if faculty organizers embraced the labor movement not simply to establish collective bargaining on individual campuses and within the property corporation’s labor-management framework, but to build a coalition of organizations that could mount pressure toward reconstitution on a grander scale? Kaufman-Osborn has shown how legal reform and labor organizing are two paths that the AAUP could have taken, and indeed did consider in its early years.31 The AAUP has, of course, since embraced labor organizing, though not explicitly as part of a broader cooperative agenda.32 Du Bois’s work suggests that such an organizing strategy might be a crucial step toward building cooperative institutions in pursuit of a more cooperative world.

Any cooperative movement in the United States would need to take heed of what the political theorist Bernard Harcourt calls the “legal coding of economic organization.” The “relationship between law and economics,” he says, “is not one of superstructure and infrastructure, but of co-constituency.” He adds that “competition or cooperation is easily constructed using the basic tools of the lawyer, enforced by government” and “the code of cooperation is just as simple as the code of capital.”33 The intricate lawyerly workings of constructing such a cooperative are beyond the scope of this article. But Harcourt, who draws explicitly on Du Bois, suggests that cooperation—already “legally coded” in many places, from housing co-ops to cooperatively owned businesses and utilities to open-source software—can have a “snowball effect.”34 What is “particularly powerful” about cooperation, he says, “is that it can build . . . in an incremental way and does not require massive collective action to transform property relations or create a common.” It can “spur more and more cooperation,” as a “virtuous circle of growth” that “does not require seizing of power, which immediately creates collective action problems in this increasingly polarized world.”35

All of this is broadly congruent with Du Bois’s vision. He had no illusions of revolutionary rupture. He was a gradualist. And he understood that marginalized Black communities—together, if unified politically, at most a kind of “nation within the nation”—were not in a position to seize the apparatus of state power.36 The Black University would take what it could get from the state, even if that meant little more than, say, legal backing for a cooperative corporate structure. But the real action was in building upon “several successful experiments,” as Du Bois put it in a letter to James P. Warbasse, founder of the Cooperative League of the United States of America.37 If the Black University sought to experiment with legal design and with more cooperative ways of mobilizing campus and community resources, perhaps proof of concept would begin to “snowball” over time, as part of a genuinely world-making movement. Who knows?

What we do know is that Du Bois’s journey in and out of the AAUP presents a cautionary tale. Some years after his departure from the professoriate and its professional organization, he turned to more alternative schools for adult education. For a period in the 1950s, at the invitation of Doxey A. Wilkerson, whose radical politics likewise led to his departure from a faculty position at Howard University, Du Bois taught African history at the Jefferson School of Social Sciences in New York.38 An unaccredited workers’ college associated with the Communist Party, the Jefferson School was short-lived, shuttered by 1956 on account of Red Scare hysteria. Notably, it was not until 1958, when Du Bois was ninety years old, that he claimed to have developed a real consciousness of himself as part of an academic working class.39 Had he remained on the faculty at Atlanta University, perhaps he would have thrown himself into the work of some of the militant unions that struggled to organize HBCU faculties in the immediate postwar years.40 In any case, the fact remains that Du Bois, one of the greatest intellectuals of the twentieth century, was pushed out of American academia. Neither labor unions nor professional organizations could protect his job status or his academic freedom. Nor could they prevent American colleges and universities from consolidating their status as bulwarks of the competitive society.

While the AAUP today is a dramatically different organization from what it was in Du Bois’s time, while it has embraced labor organizing and has become a key pillar of an ascendant academic labor movement, we ought to consider how a Du Boisian cooperative agenda might further broaden the organization’s horizons. Beyond conventional appeals to shared governance and the “good will” of trustees, how might we challenge the uncooperative structure of the modern university? What would it mean, what would it take, to hitch today’s academic labor movement to a broader cooperative movement in American society? How might “wall-to-wall” unionization and calls for a “new deal in higher education” push academic organizing beyond the paradigm of the property corporation and its labor-management framework?41 Could “several successful experiments [in] co-operation” realistically “snowball” to the point where any given community of students, campus workers, and alumni would have enough momentum to push for legal reincorporation? And, to pose a question dear to Du Bois’s legacy, to what extent are HBCUs, or perhaps new communities forged through some sort of experimental “Black University” initiative, best positioned to lead this charge?

Acknowledgments

For their very helpful comments on earlier drafts, I thank Andy Hines, Hye-Ryeon Jang, Kipton Jensen, Sam Livingston, Justin McClinton, Ella Myers, Matthew Platt, Taura Taylor, and Ulrica Wilson.

Andrew J. Douglas is professor of political science at Morehouse College and a member of the AAUP’s Committee on Historically Black Institutions and Scholars of Color. He is the author of three books, including W. E. B. Du Bois and the Critique of the Competitive Society (2019) and, with Jared Loggins, Prophet of Discontent: Martin Luther King Jr. and the Critique of Racial Capitalism (2021).

Notes

1. W. E. B. Du Bois to American Association of University Professors, March 13, 1945, W. E. B. Du Bois Papers (MS 312), Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst Libraries, https://credo.library.umass.edu/view/full/mums312-b105-i021. For additional discussion of the AAUP’s practices during segregation, see Hans-Joerg Tiede’s article elsewhere in this issue.

2. On the interconnections between anti-Black and antiradical policy and practice in the United States, including their impact on Du Bois, see Charisse Burden-Stelly, Black Scare/Red Scare: Theorizing Capitalist Racism in the United States (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2023).

3. W. E. B. Du Bois, Darkwater: Voices from within the Veil (New York: Verso Books, 2016; originally published in 1920), 18.

4. On this, and for further documentation of Du Bois’s thinking about the distinctive qualities of the “white world,” including its model of the university, see Andrew J. Douglas, W. E. B. Du Bois and the Critique of the Competitive Society (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2019).

5. W. E. B. Du Bois, “Russia and America: An Interpretation,” 1950, W. E. B. Du Bois Papers (MS 312), 7, https://credo.library.umass.edu/view/full/mums312-b221-i082.

6. See W. E. B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk (New York: Norton, 1999; originally published in 1903).

7. The pioneering concept of “abolition-democracy,” a term Du Bois used to describe the paradigm-shifting potential of the Reconstruction era, was laid out in W. E. B. Du Bois, Black Reconstruction in America: 1860–1880 (New York: Free Press, 1992; originally published in 1935).

8. See the speeches collected in W. E. B. Du Bois, The Education of Black People: Ten Critiques, ed. H. Aptheker (New York: Monthly Review, 2001), especially “Education and Work” (1930), “The Field and Function of the Negro College” (1933), “The Revelation of Saint Orgne the Damned” (1938), and “The Future and Function of the Private Negro College” (1946).

9. See Vincent Harding, “Toward the Black University,” Ebony, August 1970; Martha Biondi, The Black Revolution on Campus (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012), 142–53; Russell Rickford, We Are an African People: Independent Education, Black Power, and the Radical Imagination (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016), 168–217; Andrew J. Douglas and Jared A. Loggins, “The Lost Promise of Black Study,” Boston Review (2021), https://www.bostonreview.net/articles/the-lost-promise-of-black-study; Abdul Alkalimat, The History of Black Studies (London: Pluto, 2021), 122–27; and Joshua Myers, Of Black Study (London: Pluto, 2023).

10. Joy James, In Pursuit of Revolutionary Love: Precarity, Power, Communities (Brussels: Divided Publishing, 2023), 145, 266.

11. W. E. B. Du Bois to James P. Warbasse, August 22, 1929, W. E. B. Du Bois Papers (MS 312), https://credo.library.umass.edu/view/full/mums312-b051-i292.

12. Timothy V. Kaufman-Osborn, The Autocratic Academy: Reenvisioning Rule within America’s Universities (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2023), 3.

13. Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. “college,” accessed December 2023, https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/2519276981, and “university,” accessed December 2023, https://doi.org/10.1093/OED/4071930742.

14. See Hans-Joerg Tiede, University Reform: The Founding of the American Association of University Professors (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2015), 3, 29–30; Kaufman-Osborn, The Autocratic University, 135–62.

15. Kaufman-Osborn, The Autocratic Academy, 229.

16. See Tiede, University Reform.

17. Clyde W. Barrow, Universities and the Capitalist State: Corporate Liberalism and the Reconstruction of American Higher Education, 1894–1928 (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1990), 174.

18. Ibid., 173. On Barrow’s reading of the AAUP’s “accommodationist strategy,” see also Isaac Kamola and Eli Meyerhoff, “Creating Commons: Divided Governance, Participatory Management, and Struggles against Enclosure in the University,” Polygraph 21 (2009): 13–14, and, for a more recent analysis in line with Barrow’s, Blanca Missé and James Martel, “For Democratic Governance of Universities: The Case for Administrative Abolition,” Theory & Event 27, no. 1 (January 2024): 5–29.

19. Laura Weinrib, The Taming of Free Speech: America’s Civil Liberties Compromise (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016), 180, 150–56. I thank Andy Hines for alerting me to this history.

20. Kaufman-Osborn, The Autocratic Academy, 3, 163–64.

21. American Association of University Professors, American Association of University Professors general information, ca. 1935. W. E. B. Du Bois Papers (MS 312), https://credo.library.umass.edu/view/full/mums312-b072-i465.

22. Letter from unidentified correspondent to Ira De Augustine Reid, April 7, 1938, W. E. B. Du Bois Papers (MS 312), https://credo.library.umass.edu/view/full/mums312-b084-i373.

23. W. E. B. Du Bois to Ira De Augustine Reid, April 14, 1939, in The Correspondence of W. E. B. Du Bois: Volume II: Selections, 1934–1944, ed. Herbert Aptheker (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1976), 190.

24. W. E. B. Du Bois to Ira De Augustine Reid, May 3, 1938, W. E. B. Du Bois Papers (MS 312), https://credo.library.umass.edu/view/full/mums312-b084-i389.

25. Du Bois, “The Revelation of Saint Orgne the Damned,” 111.

26. See Herbert Aptheker’s footnote in Du Bois, Correspondence, vol. 2, 402.

27. W. E. B. Du Bois to W. R. Banks, January 11, 1944, in Correspondence, vol. 2, 391.

28. Much of Du Bois’s scholarship of this period would have unsettled the donor class. In 1936, for example, the Carnegie Corporation refused to publish “The Negro and Social Reconstruction” as part of its series of adult education booklets (see the editorial commentary in W. E. B. Du Bois, Against Racism: Unpublished Essays, Papers, Addresses, 1887–1961, ed. Herbert Aptheker [Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1985], 103). For a brief discussion of Du Bois’s “People’s College” initiatives in Atlanta, see Andrew J. Douglas, “When W. E. B. Du Bois Opened a People’s College in Atlanta,” Morehouse College Faculty Blog, February 17, 2020. Du Bois’s unsuccessful efforts to secure another academic job after his ouster from Atlanta University underscore the challenges he faced in finding an employer that would support his critical “land-grant university” study (see, for example, Du Bois, Correspondence, vol. 2, 397–401).

29. W. E. B. Du Bois, “Where Do We Go from Here? Address at the Rosenwald Economic Conference in Washington, D.C.,” in W. E. B. Du Bois’s International Thought, ed. Adom Getachew and Jennifer Pitts (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2022), 130.

30. Barrow, Universities and the Capitalist State, 173.

31. Kaufman-Osborn, The Autocratic Academy, 170–73.

32. For a discussion of the AAUP’s embrace of unionization and collective bargaining in the late 1960s, see Philo A. Hutcheson, A Professional Professoriate: Unionization, Bureaucratization, and the AAUP (Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 2000), 97–135.

33. Bernard E. Harcourt, Cooperation: A Political, Economic, and Social Theory (New York: Columbia University Press, 2023), 104. For a more comprehensive history of how capital is “coded in law,” see Katharina Pistor, The Code of Capital: How the Law Creates Wealth and Inequality (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2019).

34. Harcourt, Cooperation, 125. Note that Kaufman-Osborn likewise underscores, albeit in passing at the conclusion of his study, that to reconstitute the university as a cooperative or “member-governed corporation,” we “need only extend to the academy a possibility that the legal codes of most states already enable” (The Autocratic Academy, 271).

35. Harcourt, Cooperation, 125.

36. See W. E. B. Du Bois, “A Negro Nation within the Nation,” Current History 42, no. 3 (June 1935): 265–70.

37. W. E. B. Du Bois to James P. Warbasse, August 22, 1929.

38. For a generative recent discussion of Wilkerson and Du Bois at the Jefferson School, see Andy Hines, Outside Literary Studies: Black Criticism and the University (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2022).

39. W. E. B. Du Bois to S. Dangoulov, April 20, 1960, W. E. B. Du Bois Papers (MS 312), https://credo.library.umass.edu/view/full/mums312-b150-i319.

40. For a brief commentary on the United Public Workers of America, a racially integrated union that sought to organize several HBCU campuses and was purged from the Congress of Industrial Organizations during the Red Scare of the late 1940s, see Andrew J. Douglas, “Morehouse and the Academic Labor Movement,” Academe Blog, September 28, 2023, https://academeblog.org/2023/09/28/repost-morehouse-and-the-academic-labor-movement/#.

41. On “wall-to-wall” campus organizing, see the vision statement of Higher Education Labor United (https://higheredlaborunited.org); see also the program of the AAUP-affiliated Scholars for a New Deal for Higher Education (https://scholarsforanewdealforhighered.org).