- About

- Programs

- Issues

- Academic Freedom

- Political Attacks on Higher Education

- Resources on Collective Bargaining

- Shared Governance

- Campus Protests

- Faculty Compensation

- Racial Justice

- Diversity in Higher Ed

- Financial Crisis

- Privatization and OPMs

- Contingent Faculty Positions

- Tenure

- Workplace Issues

- Gender and Sexuality in Higher Ed

- Targeted Harassment

- Intellectual Property & Copyright

- Civility

- The Family and Medical Leave Act

- Pregnancy in the Academy

- Publications

- Data

- News

- Membership

- Chapters

Survey Data on the Impact of the Pandemic on Shared Governance

Published May 2021.

Over the course of the past year, the COVID-19 pandemic has affected higher education, including the conduct of shared governance, profoundly. In January and February 2021, the AAUP’s research department conducted a national shared governance survey of senate chairs and faculty governance leaders at four-year institutions—the first national survey about shared governance in two decades. The survey was administered to one senate chair or faculty governance leader in a similar position at each of 585 randomly-sampled four-year institutions of higher education (see technical note). The response rate was 68 percent. One part of the questionnaire concerned the impact of the pandemic on shared governance, which is the focus of this report. Reports on other findings will be released later this year.

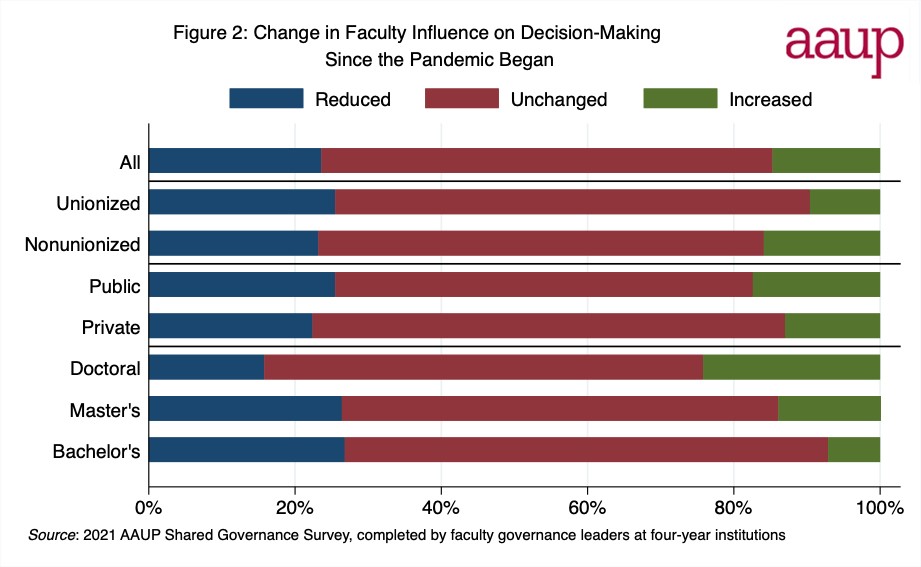

Changes in Faculty Influence

We asked respondents to report how influential the faculty had been in decision-making at their institutions both before and after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic on a scale from “not influential at all” to “extremely influential” in order to gauge how much change resulted from the pandemic (see figure 1). The largest change was in the “not influential at all” category, which increased from about 5 percent to about 10 percent across all institutions. However, somewhat surprisingly, the second largest change was in the “extremely influential” category, which increased from 5.4 percent to 6.6 percent. Overall, 23.6 percent of respondents reported a reduction in faculty influence at their institutions, and 61.7 percent reported that it was unchanged (see figure 2). It was notable that 14.7 percent of respondents reported an increase in faculty influence following the onset of the pandemic. There were differences in reported levels of increased influence by institutional type: at doctoral institutions, 24.2 percent of governance leaders reported increased influence, compared to 14 percent at master’s institutions and 7.1 percent at bachelor’s institutions.

Commenting on the increase in influence, some respondents reported a transition in leadership that coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic and resulted in changes in governance practices that might be unrelated to COVID-19. But other responses pointed to an increase in faculty influence attributable to the faculty’s being more vigilant and outspoken, as the following comment illustrates:

While I would say our influence has increased, this is not because the administration is more interested in our input. It is because the decision-making is so crucial and so much is at stake that faculty are considerably more vocal and persistent than in previous years and refuse to be ignored on health and safety issues.

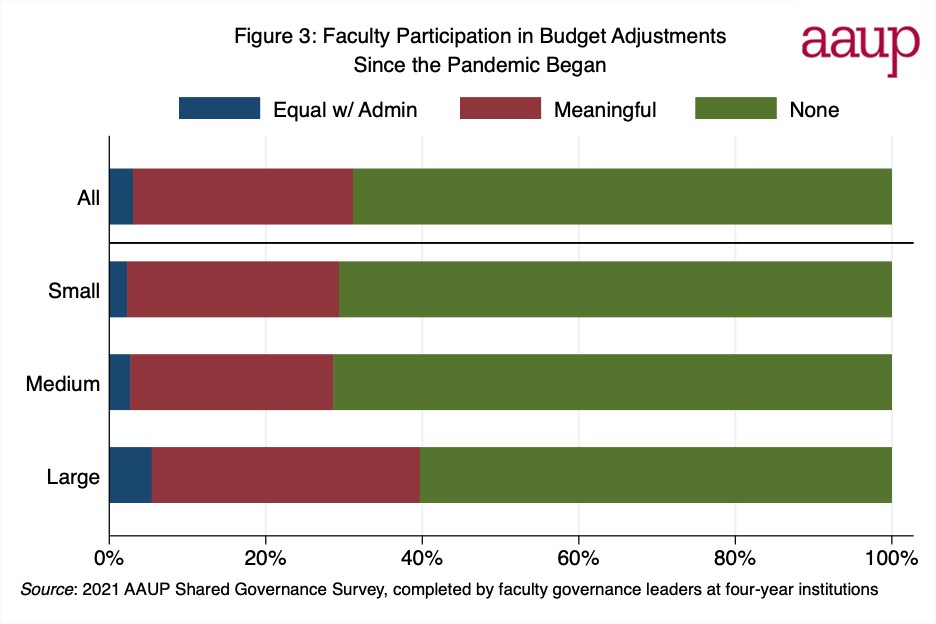

Budgetary Decisions

The survey asked about faculty involvement in budgetary decisions following the onset of the pandemic (see figure 3). Only 3 percent of respondents indicated that the faculty and administration had exercised equal influence in making such decisions. Respondents reported an opportunity for meaningful faculty participation in such decisions at 28.1 percent of institutions, while 68.8 percent reported that the administration had made such decisions essentially unilaterally. The prevalence of unilateral administrative action differed by institutional size, with governance leaders at large institutions (with more than five thousand students) reporting less unilateral administrative decision making (60.3 percent) compared to small (with fewer than two thousand students) and medium institutions (with between two thousand and five thousand students), where the prevalence of unilateral administrative decision making was 70.6 percent and 71.5 percent, respectively.

Layoffs, Program Eliminations, and “Force Majeure”

The pandemic saw faculty layoffs and program closures throughout the past year (see figure 4). Among respondents at institutions with a tenure system, 9.5 percent reported that tenured or tenure-track faculty appointments had been terminated or nonrenewed at their institution following the pandemic. Among respondents across all institutions (with or without a tenure system), 27.5 percent reported that faculty on contingent appointments had been laid off (“contingent appointments” include full-time faculty appointments at institutions without a tenure system).

Seventeen percent of respondents reported program eliminations since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Unsurprisingly, the apparent purpose of program eliminations is often to terminate the appointments of tenured faculty: among institutions with a tenure system where programs had been eliminated, 40.5 percent reported layoffs of tenured or tenure-track faculty, while only 3.3 percent of institutions where programs had not been eliminated reported such layoffs.

Although some differences between institutional types were found with respect to the prevalence of program eliminations and layoffs, they are relatively minor within the context of the margin of error. And so, while much attention during the past year has been on small private liberal arts institutions engaging in program eliminations and layoffs, the survey found that these actions were taken at about the same rates at public and private; bachelor’s, master’s and doctoral; and unionized and nonunionized institutions.

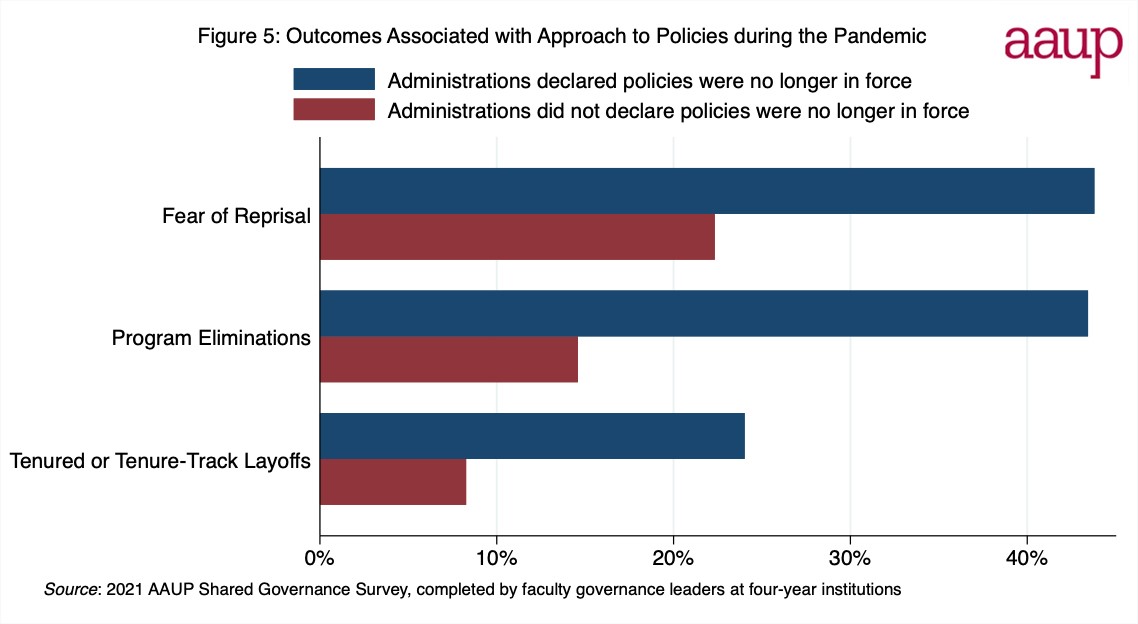

The Association has viewed with particular alarm recent instances in which administrations or governing boards declared faculty handbooks, other institutional regulations, or parts of collective bargaining agreements as no longer in force, at times due to an invocation of “force majeure” or “act of God.” Respondents from 9 percent of institutions reported that, since the beginning of the pandemic, their administrations or governing boards declared institutional regulations to be no longer in force. It is apparent that declarations that regulations are no longer in force are commonly used to effect program eliminations and terminations or nonrenewals of tenured or tenure-track faculty appointments. At institutions where regulations had been declared no longer in force, 43.4 percent of respondents reported the elimination of programs, compared to 14.6 percent of respondents at institutions where regulations had not been voided. Similarly, at institutions with a tenure system where regulations had been declared no longer in force, 24 percent reported the termination or nonrenewal of tenured or tenure-track appointments, compared to 8.3 percent reported by those at institutions where no action had been taken to declare regulations no longer in force.

Governance Climate and the Pandemic

One measure of the health of a governance system is whether faculty members can voice dissenting opinions without fear of administrative reprisal. The questionnaire asked governance leaders for their assessment of whether faculty can voice dissenting opinions at their institution without such fear. Overall, 24.2 percent of respondents indicated that they felt that faculty members could not voice dissenting views without fear of administrative reprisal.

The Association’s concern over unilateral actions to declare institutional regulations as no longer in force is heightened when considering what occurred at those institutions as compared to institutions that did not make such declarations (see figure 5). At institutions where the administration or board declared regulations no longer in force, 43.8 percent of governance leaders indicated that faculty could not voice dissenting views without fear of administrative reprisal, compared to 22.3 percent at institutions where no regulations had been voided. At institutions where respondents reported an increase in faculty influence, 14.1 percent indicated that faculty are not able to voice dissenting views without fear of administrative reprisal, compared to 23.9 percent at institutions where faculty influence was unchanged and 31.3 percent at institutions where it had decreased.

Conclusion

The results of the survey provide additional evidence for the observation in the recent AAUP governance investigation that “shared academic governance has been under severe pressure since the onset of the pandemic.” Nearly 10 percent of institutions with a tenure system have laid off tenured and tenure-track faculty since the onset of the pandemic, and more than a quarter (27.5 percent) of institutions have laid off faculty on part-time or full-time non-tenure-track appointments. In addition, 17 percent of institutions have eliminated academic programs during the pandemic, and close to one in ten have declared some or all institutional regulations no longer in force. These figures speak to broader trends regarding the impact of the pandemic on shared governance.

On the other hand, the survey also found an increase in faculty influence at some 15 percent of institutions, which apparently resulted, at some of these institutions, from faculty members being more vigilant and outspoken. These findings complement those of the governance investigation in a different way, as they point to ways in which faculties were able to respond successfully to the challenges of the pandemic through shared governance channels. As the AAUP governance investigation noted, “governing boards, administrations, and faculties must make a conscious, concerted, and sustained effort to ensure that all parties are conversant with, and cultivate respect for, the norms of shared governance as articulated in the Statement on Government of Colleges and Universities” in order for shared governance to survive.

Technical Note

The population to which the results of this study are intended to be generalized and from which the sample was drawn consists of 1,422 institutions of higher education that are classified as bachelor’s, master’s, or doctoral institutions in the Carnegie classification system. The AAUP Research Department administered the questionnaire to senate chairs and faculty governance leaders in a similar role at a stratified random sample of 585 institutions. The data were weighted to account for different probabilities of selection during sampling between different strata and to account for nonresponse. Estimates of proportion in the population made on the basis of a sample have a margin of sampling error. The margin of sampling error depends on the sampling design (the “design effect”), the size of the sample, and on the estimated proportion itself. With 396 respondents in this stratified sample, it is +/- 4.3 points when the proportion reported is 50 percent, which is when the margin of error is largest for a given sample size.