- About

- Programs

- Issues

- Academic Freedom

- Political Attacks on Higher Education

- Resources on Collective Bargaining

- Shared Governance

- Campus Protests

- Faculty Compensation

- Racial Justice

- Diversity in Higher Ed

- Financial Crisis

- Privatization and OPMs

- Contingent Faculty Positions

- Tenure

- Workplace Issues

- Gender and Sexuality in Higher Ed

- Targeted Harassment

- Intellectual Property & Copyright

- Civility

- The Family and Medical Leave Act

- Pregnancy in the Academy

- Publications

- Data

- News

- Membership

- Chapters

The AAUP and Academic Freedom at Grambling

Looking back at the AAUP’s work at one historically Black institution.

Wednesday, March 27, 1968, started the same as pretty much any other day for Antonia Hacker.1 She got up, left the small house she shared with the local librarian, and walked to her job. She taught art at Grambling College, a historically Black college in the small town of Grambling, Louisiana. Hacker went about her day normally until she was called into the president’s office and unceremoniously dismissed from her faculty position.2 Stunned, Hacker learned that President Ralph Waldo Emerson Jones refused to honor her contract, even after it had automatically renewed.3 After Jones yelled at her and accused her of spreading radical ideology among the students, Hacker returned to her rented room and began the process of moving back to her native California.4

Hacker was not the only Grambling faculty member summarily dismissed that day. Joyce B. Williams and Jane E. Morrow felt the ire of the college president as well. Also fired in violation of their contracts, the women would eventually ask the AAUP to investigate their dismissals. The move to terminate the faculty appointments of these three individuals stemmed from their alleged involvement in the events that occurred in fall 1967 and fit into a broader pattern of the Grambling administration’s rejecting academic freedom and chilling free expression.

This article revisits the findings of the AAUP investigation, published more than fifty years ago in the AAUP Bulletin. That report, while prompted by the dismissals of the three faculty members, marginalized their voices in favor of a narrow reading of academic freedom that hinged on the date of renewal of their contracts. In what follows, we seek to shed new light on the significance of the events at Grambling by rereading the AAUP’s investigative report alongside student leader memoirs and student and faculty oral histories. In so doing, we will situate academic freedom at Grambling in the context of larger questions about how historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) negotiated Black campus activism during the civil rights movement.

Academic Freedom at Grambling in the 1960s

In the 1960s, tenure and academic freedom were, for the most part, foreign concepts at Grambling College. The administration censored the student newspaper, and it frequently dismissed faculty members for participating in off-campus civil rights activity. The most telling example is the case of Frederick Douglass Kirkpatrick. A Grambling alumnus from Simsboro, Louisiana, Kirkpatrick took a job teaching physical education at Grambling in 1966. While on the faculty, he led a number of protests both on and off campus. In particular, he led a group of students who called themselves the Great Society Movement. This group tested restaurants in nearby Ruston for compliance with desegregation legislation. The group picketed and put together plans to sue the restaurants that failed to comply.5 Before Kirkpatrick could finalize the plans to file the lawsuits, white power brokers in Ruston allegedly contacted Jones and insisted that he fire Kirkpatrick and two of his allies on the faculty. President Jones obliged.6

Owing to Grambling’s location in a small, nearly entirely African American town in rural Louisiana, Jones held a tighter level of control over the campus than most other HBCU presidents, including power over the off-campus activities of faculty and students. Jones was a part owner of the only grocery store in town, which he used to provide jobs to favored students.7 The mayor of the town, the preacher at one of the largest churches, and several other community leaders were on the college’s payroll.8 Jones had the power not just to expel a student or fire a faculty member but to drive them out of town as well. When the aforementioned pastor, Mose Pleasure Jr., the preacher of Jones’s church, criticized his heavy-handed methods during protests, Jones had the preacher fired and forced him out of the community.9 When students were expelled, Jones demanded that no landlord in the town allow them to rent an apartment. Jones threatened to prohibit all future students from renting from any landlord who defied his edict.10 Jones used his uncommon power to drive at least six faculty members out of the community between 1966 and 1968.11

In 1967, Grambling’s campus exploded in a massive student demonstration that took over several buildings, threatened to disrupt the homecoming game, and involved about 2,500 of the 4,000 students on campus. The reluctance of Grambling’s administration, particularly President Jones, to adapt to a changing world drove the student dissatisfaction. Students, led by a group of members of the Student Government Association who called themselves “The Informers,” demanded that the administration make a number of specific policy changes and improvements on the campus. Students protested for, among other things, higher-quality—and insect-free—food in the cafeteria, better-qualified faculty and administrators, a greater emphasis on academics than on athletics, and a relaxation of gender-based rules that tightly restricted the activities of female students on and off campus.12

More than anything else, though, the protests focused on the actions of President Jones himself, whom the Informers described as “a prince whose character is thus marked by every act which may define him as a tyrant.”13 HBCUs, especially the public institutions that operated under the auspices of segregated southern governments, had developed a reputation for tyrannical leadership. Presidents of several HBCUs in the 1960s became infamous for suppressing academic freedom and other forms of free expression in order to appease the white politicians who paid their salaries. In particular, Felton Clark, the president of Southern University in Baton Rouge, drew faculty ire. After the Congress of Racial Equality tried to stage a massive protest at Southern in December 1960, Clark expelled protesting students and accused them of being “culturally void,” while demanding that the faculty acquiesce and not act like “the dog that bit the hand that fed it.” One faculty member was so taken aback that he wrote a ten-page letter of resignation that accused Clark of hiding behind the same defense as Nazi war criminals—“he was only obeying orders.”14 Famous southern historian C. Vann Woodward similarly bashed Clark in Harper’s.15 Like his counterpart to the south, Jones took a heavy-handed approach when Grambling faced massive student protests in north Louisiana.

The protests were large enough to scare Grambling’s administration into requesting the National Guard and to garner coverage in several national publications.16 Louisiana governor John McKeithan dispatched two liaisons to try to defuse the situation. Once the protests ended, Grambling College meted out discipline. It expelled dozens of students—in several cases without any evidence of their involvement—and slowly took steps to address some of the student concerns. For unknown reasons, however, the administration waited until March to act against those faculty it suspected of taking part in the protests.

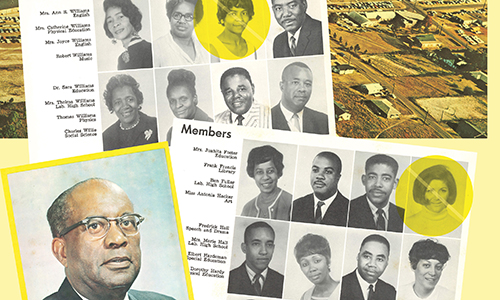

In this climate, the AAUP may seem like an organization that would not have been welcome at Grambling. However, an AAUP chapter had existed at Grambling since 1961.17 Its activities remain largely obscured, but the chapter had a broad membership representing the college across many disciplines. The twenty founding members of the chapter represented at least eleven disciplines. Several of them were department heads, and several others received promotions over the course of the decade, including the founding president, Lamore Carter.18 Carter, who had a long and distinguished career in higher education, ended his career at Grambling as provost.19 Jones appears to have had little problem with the chapter or the members.

The national organization did take seriously the threats to academic freedom that came from HBCU presidents like Jones.20 Though viewed with suspicion in southern states that saw national organizations working to preserve constitutional freedoms as existential threats to their white supremacist regimes, the AAUP made some significant efforts to protect academic freedom at southern HBCUs.21 In 1964, for example, the AAUP was one of several national organizations to defend Tougaloo College when the Mississippi legislature attempted to revoke its charter and strip its graduates of the ability to gain teaching licenses in the state. Thanks in part to effective advocacy from the AAUP, both efforts failed.22

In 1969, at the same time that it was investigating the dismissals at Grambling, the AAUP started a broad effort to expand its activities on HBCU campuses. Initially funded by a Ford Foundation grant, the Special Project for Developing Institutions (SPDI) sought to “assist those black colleges and universities which desired advice and assistance relating to academic freedom and tenure and college and university government.” The Association itself noted that “historically, the AAUP has not always seemed credible to constituents in black institutions.” The AAUP’s early success at establishing a chapter at Grambling undoubtedly gave the project a head start on the campus.23

Among other pertinent issues, the AAUP was deeply concerned about academic freedom at HBCUs. Colleges like Grambling had particularly poor records of respecting academic freedom and free speech. As one conservative African American critic of HBCUs, J. Saunders Redding, once stated, “Negro colleges have tended to breed fascism,” and their presidents “play the strongman and the dictator role.” According to Redding, HBCU presidents “think that people and things should be ‘lined up’ by the superior intellects which they feel their positions endow them. . . . They have a vast contempt for faculty members whom they regard as justly underprivileged employees perhaps of somewhat more value than janitors but of considerably less value than football coaches.” Redding, a professor himself, believed that a lack of faculty governance in HBCUs was partly to blame for the subordination of African Americans. He wrote,

Presidential contempt engulfs students, who grow into maturity with personalities habituated to submission and who are likely to believe in the infallibility of dictatorship principle. . . . Negro-educated Negroes have never learned to live with Freedom and this is why they are almost totally missing from the ranks of those who apply the privileges and the tools of democracy to the construction of Freedom’s spacious houses. . . . Where they have taken over as leaders of Negro communities there rises a nauseating reek of devious and oily obsequiousness. . . . It is a kind of fascism in reverse.24

Elements of Jones’s presidency exemplified this model, and it was this system that the AAUP wanted to break.

The successes of the Black freedom struggle in the 1960s, paired with a growing African American consciousness on HBCU campuses, gave the AAUP the impetus to lend its hand to a major reform of HBCUs. The SPDI, a limited proof-of-concept endeavor, dedicated most of its efforts to helping HBCUs implement the standards set forth in the 1940 Statement of Principles on Academic Freedom and Tenure and the 1966 Statement on Government of Colleges and Universities.25 The core AAUP values articulated in these statements were radically new for institutions like Grambling. Unfortunately, no documentation appears to exist about the national AAUP’s work at Grambling, but there is no doubt that the organization achieved some meaningful successes. In the 1970s, Grambling established tenure, abandoned its long-standing policy of administrative censorship of the student newspaper, and ceased the practice of terminating faculty appointments for political speech or other extramural activities. The reforms came too late to help those whose appointments had been terminated in 1968, but it is likely no coincidence that the AAUP, along with student activists, achieved positive changes in the institution in the years following the investigation. Grambling’s dismissed faculty members were martyrs for academic freedom.

The Dismissals

The three faculty members dismissed by Grambling had, at best, a limited role in the 1967 protests. Joyce Williams provided encouragement to the students and was sympathetic but never participated herself. Jane Morrow allowed expelled students to use her house as a meeting place and helped them apply to colleges in New York and California. In particular, she helped arrange a visit from a University of California recruiter who brought applications and helped expedite the transfer process. Morrow required that the recruiter come to her house at night, out of fear that her neighbors would inform Jones.26 Antonia Hacker, an artist at heart, spent the days of the protest roaming around campus photographing the students.27

Of the three faculty members in question, Williams was the only African American. President Jones harbored a deep suspicion of outsiders on campus and was particularly distrustful of white activists. The first white student at Grambling, Mary Jamieson, was an activist from New York.28 Although Jones was pleased with civil rights attorney A. P. Tureaud and the NAACP for breaking the legal prohibition of non–African American students at Grambling, he did not appreciate Jamieson’s activism.29 Likely because she joined with students who accused Jones of being an Uncle Tom, Jamieson earned his scorn early in her time at Grambling. She participated in many protests, both on and off campus, during the summer of 1965. His disdain for Jamieson and other white students and faculty probably stemmed in part from his belief that “outsiders” were constantly looking to stir up trouble on a campus that he believed was his to control.30

By contrast, Jones’s decision to terminate the faculty appointment of Joyce Williams, an African American woman, was linked to personal trouble between the two of them. Williams, an assistant professor in the English department, had taught at Grambling for several years before the protests started and established a reputation as a faculty member who cared deeply about students and their well-being. Although her appointment was nominally terminated for her “failure to meet the expected level of loyalty and dedication to the teaching profession,” Jones told Williams that he believed she was “not loyal to the school” and that she had “assisted the student leaders during the recent demonstration at the college.” She denied both claims, as did student leaders.31 We know that she was present during the events, since she was named among a list of potential witnesses during the student discipline hearing at Grambling on November 27, 1967. However, so too were other prominent members of the college community, including the head football coach, Eddie Robinson.32

Williams was convinced that the real reason for her dismissal was personal and that the protests merely provided a convenient pretext.33 In his memoirs, Willie Zanders, one of the student protest leaders, provides a possible different explanation for why Joyce Williams was among the three faculty members dismissed from the college in 1968. Jones, a widower, had unofficially adopted the thirteen- or fourteen-year-old son of two janitors who worked for him at the college. According to one contemporary, the parents “gave the president full control over him, thus enabling them to use their small salaries to care for their other children.” Although a college president’s adoption of the teenage son of two underpaid employees would be viewed with suspicion at most institutions, Jones had such a hold on the institution that no one would suggest that there was even an appearance of impropriety.34

Williams’s own son, twelve years old at the time, was a friend of Jones’s “adopted” son. The two boys played together frequently. One unfortunate day, however, the two of them allegedly were playing at Jones’s on-campus house when a shotgun was fired, killing Williams’s son. When Williams went to Jones to inquire about insurance coverage that might compensate her for the death of her son, Jones became “very defensive and uncooperative. . . . He said he had no control over the boy’s actions, and that his hands were clean.” Jones recommended that Williams contact his “adopted” son’s parents, which she did. Being working poor employees of Grambling, they had no means with which to compensate Williams for the loss of her son. When Williams tried to speak again with Jones about the matter, “he refused to make an appointment to see [her].” She then attempted to hire a lawyer but found that no one would take her case. Louisiana’s nearly all-white bar had few attorneys willing to take cases for African American clients, and even fewer were willing to take a case against an African American like Jones who was popular for his racially accommodationist policies, even if he may have shared liability for the death of a child. When Williams tried to hire an attorney to force Jones to account for the accident, she said, “They told me that the President was a real powerful man, well known and well-liked by people in powerful positions.”35

Williams believed that the death of her son was the real reason for her dismissal. “The recent student demonstrations were his first opportunity to get rid of me, so he claims I took sides with the protestors and helped behind the scenes. . . . That was totally untrue,” Williams said. She argued that while she knew the students involved, including the leaders, she “knew nothing of their plans to boycott classes or take over the buildings until it actually happened.” Williams claimed that “teachers talked to them from time to time, . . . but to my knowledge, no one helped them.”36 Her statement is corroborated by both the memories of participants and contemporary court documents, none of which even hinted at the involvement of faculty members in the protests.37

After being dismissed, Williams once again sought an attorney—this time to get her job back. Again, she failed to find a local attorney willing to take on her case. One of the attorneys she contacted suggested that she reach out to the AAUP, which she did. Williams, along with Morrow and Hacker, filed a complaint with the Association.

AAUP Investigation

The AAUP conducted a comprehensive inquiry in which an investigating committee visited the college and met with Jones and several members of the Grambling faculty. Noting that the college had recently adopted a standard date of reappointment of March 1, the AAUP committee sought to determine why the college arbitrarily ignored that date when it terminated the faculty appointments of the three women. Jones himself had informed the AAUP in October 1967 that Grambling would use March 1 as the date for automatic reappointment at the behest of Grambling’s AAUP chapter: “a committee of our local AAUP members approached the Dean of the College about the possibility of changing our date of April 30 to March 1, so that we could be in line with AAUP, when it comes to notifying one about a termination of his service. . . . The Dean and I conferred and agreed to accept March 1 as the date to which Grambling College will adhere, beginning July 1, 1967.”38 Jones immediately ignored the new policy when he dismissed the three faculty members.

When the investigators questioned Jones about why he ignored the March 1 date, he gave a litany of unconvincing excuses, none of which he had previously provided to the dismissed faculty members. Jones said that since the State Board of Education was hearing the cases of expelled students, and it was possible that the three women could be mentioned in testimony, the notices of termination should be sent after the hearing concluded. He claimed that “someone in the State Attorney General’s office had so advised him in a telephone conversation.” Aside from the fact that the board hearing had concluded in December 1967, Jones had a demonstrated tendency to tell self-serving lies, and it is unlikely that anyone from the state attorney general’s office would have been involved in such a mundane matter.39 Even so, the investigating committee determined that the three women “were not principals in those proceedings; they were not in any way apprised of a relationship between the hearings and possible issues with regard to their continuance on the faculty of Grambling College; and there is no indication that any materials introduced at the hearings reflected upon them.”40 The considerable court documentation that the protests produced—none of which the investigating committee had access to—proves the AAUP correct. None of the three women are mentioned in any of the voluminous testimony or introduced evidence. The investigative report declared that “there was . . . no justification for an unannounced delay of decisions respecting their status pending a proceeding in which they were not involved.” Further, the investigating committee’s report stated that “the summary action to terminate their services is of grave concern to the Association and to the academic community generally.”41

The faculty members were also denied academic due process. Based on AAUP-recommended standards that Grambling had recently adopted—no doubt thanks to the efforts of the local chapter and members—any faculty member dismissed after March 1 was to be afforded the protections of academic due process, and a dismissal then could be only for cause. Grambling also ignored due process with regard to the student expulsions.42 Even though Jones was open to reforming policies to align with AAUP-supported standards, he remained committed to the belief that the college belonged to him. At one point in disciplinary hearings with students, Jones went so far as to deny that he had any obligation to comply with federal court orders.43

The investigating committee dedicated about half of its report to violations of academic freedom. The 1940 Statement of Principles explicitly states that academic freedom must apply equally to non-tenure-track and tenure-track faculty. Williams, Morrow, and Hacker all complained that the administration had violated their academic freedom when it dismissed them. Although Williams believed that Jones dismissed her because of the accidental killing of her son, Jones made it perfectly clear to each of the women that the official reason for the termination of their services was their alleged participation in the protests. Jones “spoke at considerable length” with the AAUP staff and the investigating committee, “and in his remarks he linked each of the three to the October demonstrations in differing degrees.” The committee concluded that “there are no major conflicts between his testimony and that given by the three in terms of what they actually said and did at the time of the demonstration.” Jones agreed with the report’s final conclusion that regardless of what any official paperwork may have stated, the dismissals were the result of the activities of the three women during the protests.44

The AAUP condemned Jones’s decision to terminate the appointments because “the faculty members’ activities, insofar as the investigating committee could ascertain . . . , were undertaken with a considerable measure of dignity, proceeded from compassion for and empathy with the students, involved no absence from classroom or other professional responsibilities, and in no other way departed from recognized standards of responsible faculty conduct.” The committee found that the faculty members’ activities consisted of nothing that should have reasonably resulted in dismissal. Jones accused the women of remarkably mundane actions—“taking a snapshot, responding with a smile, talking with a member of the press, giving assistance to an expelled student”—that should have been protected under the umbrella of academic freedom. Jones, however, interpreted these actions as “manifestations of an attitude that was in some manner ‘disloyal’ to the administration of Grambling College.” He responded to the committee’s written report with characteristic scorn for those who questioned him: “It is apparent that the investigating committee attempted to play down the magnitude of the role played [by the faculty members] in encouraging the student leaders. . . . Anyone who encouraged the type of campus unrest as described above could not by any stretch of the imagination have acted in a dignified manner.” Jones remained obstinate, maintaining that merely photographing the protests or responding to protesting students with a smile meant that a faculty member was encouraging the protesters.45

The committee concluded that “the expected standard of loyalty implied by President Jones is . . . out of keeping with a free academic community.” “The relationships between the dismissed faculty members and the demonstrating students . . . appear to have been unexceptional,” the committee’s report continued. Emphasizing that the college never put forth any evidence that showed any meaningful encouragement of the protesters, the committee argued that the dismissals “necessarily [have] a chilling effect on academic freedom, an effect substantially compounded by the unavailability of academic due process for the faculty members concerned.”46

Since Jones had no evidence that the faculty members actually encouraged the protests, Williams’s belief that the terminations were rooted in something else rings true. Certainly, other faculty members must have smiled in the direction of protesters, and the court documents include photographs taken of the protests by other faculty members.47 Jones had a compelling reason to remove Williams from the community, but his motives for dismissing Hacker and Morrow remain unclear. Hacker, who was from an activist family and admitted to attending protests prior to her arrival at Grambling, argues that she was not an activist herself. However, she had friends who were, and she had been in an interracial relationship with an African American man.48 It is plausible that Jones found that behavior threatening to his vision for the Grambling community. The president’s motivation in Morrow’s case, unfortunately, remains more obscure. Other than her having been white and not from the local area, there is little that we can say about her apart from Zanders’s account of the assistance she rendered to expelled students applying to colleges outside of the South.49

Conclusions

The AAUP’s investigating committee issued a terse conclusion to its report in which it agreed entirely with the faculty members, concluding that Grambling both violated their academic freedom and denied them the academic due process to which they were entitled under Association-recommended standards.50 Although the report avoided specific recommendations, the AAUP voted to censure the administration of Grambling College for its actions.51 It was not until the late 1970s—after Jones retired—that Grambling worked with the AAUP to establish procedures to ensure that faculty would not be disciplined in violation of their academic freedom and to guarantee due process in cases of severe faculty discipline. Under Jones’s successor, Joseph Johnson, Grambling made substantial enough progress that the AAUP agreed to remove it from the list of censured administrations. Perhaps just as significant, Johnson apologized to the dismissed faculty members, writing to the widower of Joyce Williams that Grambling “now assures due process in a case such as hers and expresses regrets that these protections were not in place when the previous administration acted to terminate her services.”52

Although the AAUP failed to persuade the administration to reinstate the faculty members, the Association’s efforts helped to improve the quality of life for faculty at Grambling. When it came to faculty affairs, Grambling College in the 1960s was still an emerging institution. Its president, Ralph Jones, acted as if the college was his personal property, and his summary dismissals of these three faculty members were just one manifestation of his autocratic view of governance. With the help of the local AAUP chapter, and following the investigation by the national AAUP, Grambling eventually reformed its policies and brought them into line with national standards. More broadly, the AAUP’s efforts to reach out to HBCUs and work with them at a time when taking such actions was controversial helped integrate these institutions into the broader American academic community.

Brian M. McGowan is assistant professor of history at the University of Arkansas. He writes about African American history and education. His email address is [email protected]. Edward L. Holt is the department head of history and holds the Benjamin A. Quarles Endowed Professorship at Grambling State University. His email address is [email protected].

Notes

1. Research for this project was conducted as part of the “Voices of Grambling” initiative. Support for this phase of the project has been made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) in partnership with the Social Science Research Council (SSRC). Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this article do not necessarily represent those of the NEH or the SSRC. The authors would like to thank these funders as well as Yanise Days and all of the students who have taken part in the “Voices of Grambling” initiatives.

2. Toni Rodriguez (née Antonia Hacker), interview by Brian McGowan, September 2022, recording, Voices of Grambling, History Department, Grambling State University, Grambling, LA.

3. “Academic Freedom and Tenure: Grambling College (Louisiana),” AAUP Bulletin 57, no. 1 (1971): 51.

5. National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, Office of the Field Director of Louisiana records, Amistad Research Center, New Orleans, LA.

6. “Rights Fighting Profs Fired; Student March,” Chicago Defender, July 30, 1966, 32.

7. Lawyers Constitutional Defense Committee (LCDC), Zanders v. Louisiana State Board of Education, Tougaloo College, Jackson, MS, untitled Informers pamphlets included in “Transcript of Hearing before the Louisiana State Board of Education.”

8. “Zanders v. Louisiana State Board of Education,” 1968, Box 20-1, National Archives and Records Administration, Fort Worth, TX, exhibits included with “Transcript of Hearing before the State Board of Education.” It should be noted that often these individuals had roles as educators at the university; this was the case for the mayor in question: Bennie T. Woodard. Martha Woodard Andrus, interview by Yanise Days, January 2024, recording, Voices of Grambling, History Department, Grambling State University, Grambling, LA.

9. LCDC, Zanders v. Louisiana State Board of Education, Tougaloo College, Jackson, MS, press clippings.

10. Willie M. Zanders, 67 Days in 1967 (printed by the author, 2022), 166.

11. Chicago Defender, July 30, 1966, 32; “Academic Freedom and Tenure: Grambling College (Louisiana).”

12. Brian M. McGowan, “Black Power and Student Protest against Uncle Tomism at Grambling College,” in Sport and Protest in the Black Atlantic, ed. Michael J. Gennaro and Brian M. McGowan (New York: Routledge, 2023), 133–35.

13. LCDC, “Declaration of Intent.”

14. Adam Fairclough, Race and Democracy: The Civil Rights Struggle in Louisiana (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1995), 290–91.

15. C. Vann Woodward, “The Unreported Crisis in Southern Colleges,” Harper’s Weekly, October 1962, 86.

16. New York Times, October 29, 1967, L83; Chicago Defender, October 30, 1967, 5; Jet, November 16, 1967, 20.

17. Gramblinite, November 4, 1961.

18. The careers of these individuals can largely be tracked in the faculty rosters located in Grambling College yearbooks from 1961 to 1968. Starting in 1969, these yearbook photo rosters no longer exist for the larger faculty body but remain for individuals in the role of department heads and in senior administration.

19. “Lamore Carter Reflects on Half a Century in Higher Education,” accessed January 15, 2024, https://www.gram.edu/news/index.php/0000/00/00/lamore-carter-reflects-on-half-a-century-in-higher-education/.

20. For a discussion of other HBCUs that dismissed faculty members in violation of their academic freedom, see Joel Rosenthal, “Southern Black Student Activism: Assimilation vs. Nationalism,” Journal of Negro Education 44, no. 2 (1975): 124–25.

21. Fairclough, Race and Democracy, 432.

22. Joy Ann Williamson, “Black Colleges and Civil Rights: Organizing and Mobilizing in Jackson, Mississippi,” in Higher Education and the Civil Rights Movement, ed. Peter Wallenstein (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2008), 130.

23. Donald Pierce, “Report of Committee L, 1973–74,” AAUP Bulletin 60, no. 2 (1974): 244.

24. J. Saunders Redding, On Being Negro in America (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1951), 11.

25. “Report of Committee L, 1973–74,” 244.

28. Mary Barnes (née Jamieson), interview by Brian McGowan, September 28, 2022, recording, Voices of Grambling, History Department, Grambling State University, Grambling, LA, https://rss.com/podcasts/voicesofgrambling/635261/. For more on Mary Barnes and the desegregation of Grambling College in 1965, see Brian McGowan, “Integrating Grambling: Mary Barnes and the Louisiana Civil Rights Movement,” 64 Parishes, accessed March 4, 2024, https://64parishes.org/integrating-grambling.

29. Rachel L. Emanuel and Alexander P. Tureaud Jr., A More Noble Cause: A. P. Tureaud and the Struggle for Civil Rights in Louisiana, A Personal Biography (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2011), 190.

30. John Pope, “The Prez: He Played It Cool,” Washington Post, June 5, 1977.

31. Zanders, 67 Days, 145; Ken Armand, interview by Brian McGowan, April 2022, recording, Voices of Grambling, History Department, Grambling State University, Grambling, LA.

32. “Hearing before Discipline Committee Grambling College,” November 27, 1967, 7.

34. Ibid., 147. Even today, members of the Grambling community are reluctant to discuss Joyce Williams or this incident.

37. Neither the copious records from the federal court case nor the associated files of the students’ lawyers contain anything that implicates nonstudents. Zanders v. Louisiana State Board of Education, National Archives and Records Administration, Fort Worth; LCDC, Zanders v. Louisiana State Board of Education, Tougaloo College, Jackson, MS.

38. “Academic Freedom and Tenure: Grambling College (Louisiana),” 51.

39. Ibid., 51–52. Jones lied under oath in his own testimony before the State Board of Education and in the case that resulted in the admission of Mary Jamieson in 1965. LCDC, Zanders v. Louisiana State Board of Education, Tougaloo College, Jackson, MS, Transcript of Hearing before the State Board of Education; Mildred B. G. Gallot, A History of Grambling State University (Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1985), 101.

40. “Academic Freedom and Tenure: Grambling College (Louisiana)," 52.

42. Zanders v. Louisiana State Board of Education, National Archives and Records Administration, Fort Worth, “Opinion of the Court.”

43. McGowan, “Black Power and Student Protest,” 140–41.

44. “Academic Freedom and Tenure: Grambling College (Louisiana),” 52.

47. LCDC, Zanders v. Louisiana State Board of Education, Tougaloo College, Jackson, MS, has copies of several photographs that were entered into evidence of student protesters. Although the photographs had been taken by Grambling College employees, their names are not included.

50. “Academic Freedom and Tenure: Grambling College (Louisiana),” 52.

51. “Developments Relating to Censure by the Association,” AAUP Bulletin 61, no. 1 (1975): 26.

52. Matthew W. Finkin, “Report of Committee A, 1980–81,” Academe, August 1981, 179.